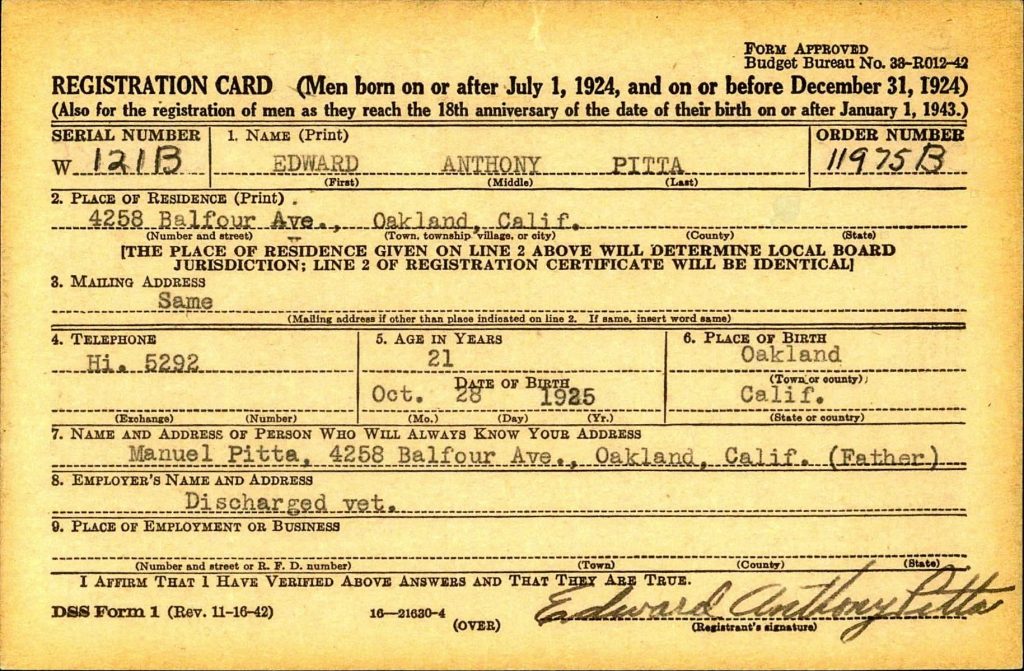

There were two, and apparently just two, rearming boats on hand at Midway on 13 February 1944, boats Nos. 1 and 3. Each was manned by a crew of two. In boat No. 1 were Seaman 1/c LeRoy Benny Lehmbecker and Seaman 2/c Howard Eugene Daugherty. In boat No. 3 were Seaman 1/c Ernest David Samed and Seaman 2/c Edward Anthony Pitta.

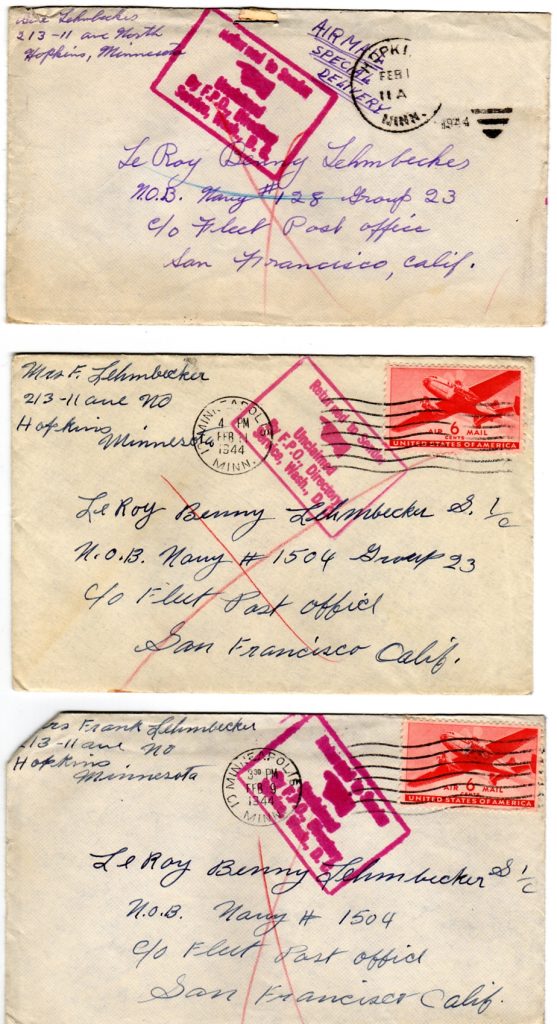

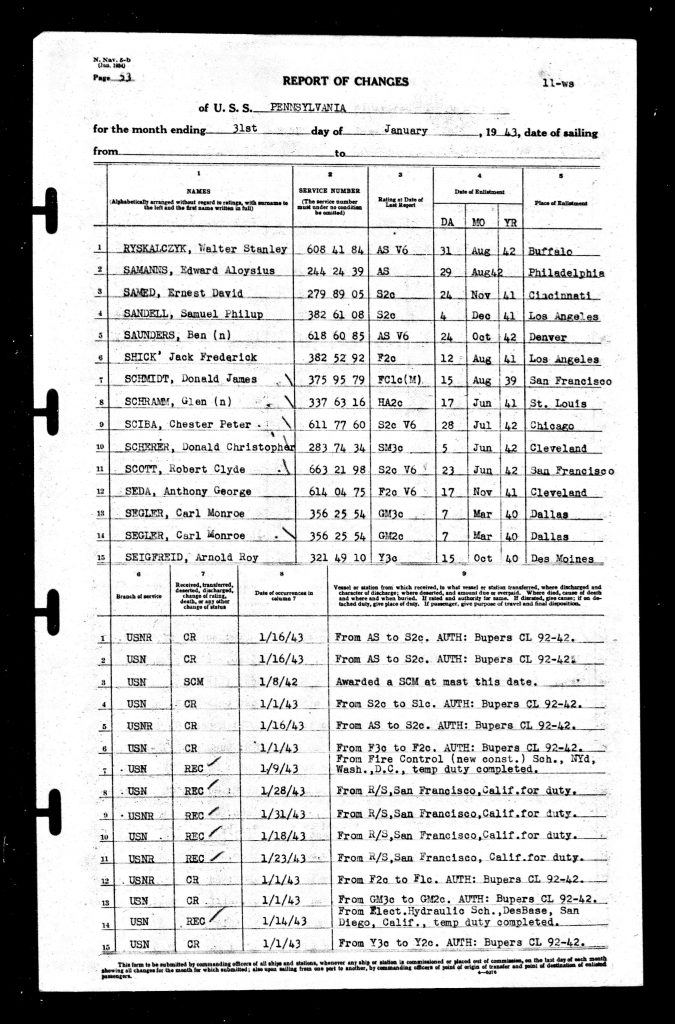

Samed held the rating of seaman first class despite the fact that he had been found guilty of resisting arrest by a shore patrol at a deck court aboard the battleship USS Pennsylvania a little more than a year before, docked forty dollars in pay, and transferred off the ship, first to Pearl Harbor, then to NOB (Naval Operating Base) Midway. Samed’s exact date of birth is unknown. He was nineteen or twenty. His father, David (originally Daoud), immigrated to the US in 1905 from Syria, then a part of the soon-to-implode Ottoman Empire.

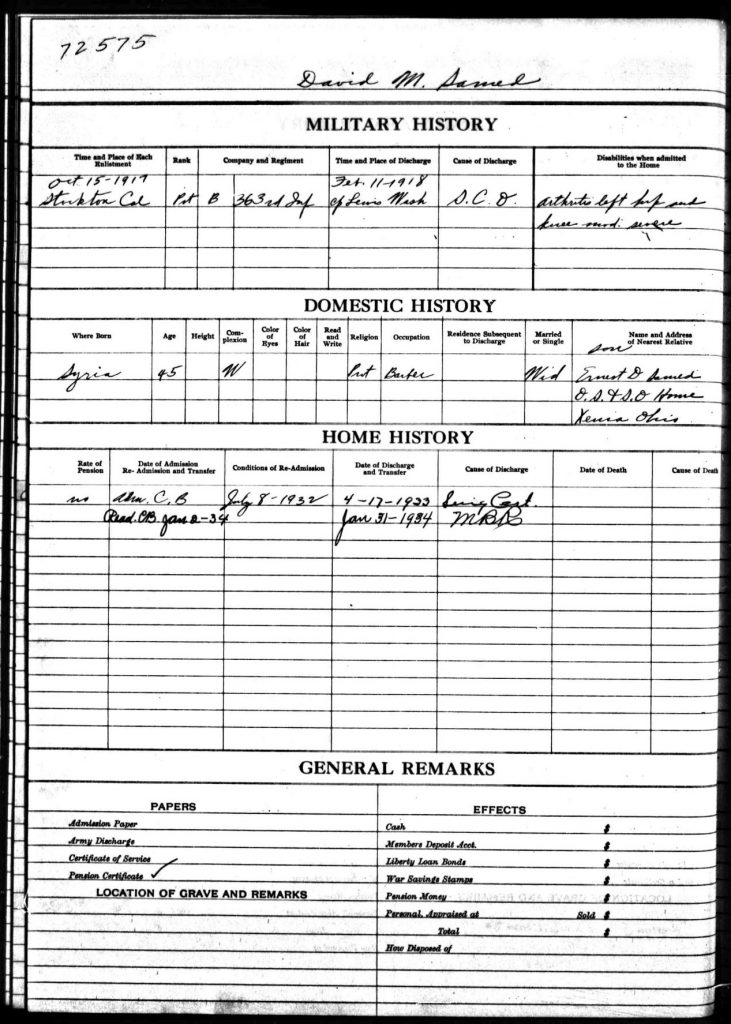

David Samed worked as a barber in Tracy, California, a Central Valley town about fifty miles east of San Francisco, served briefly in the US Army, then moved to Cincinnati, where he appears to have worked as an auto mechanic, and where, on 21 May 1920 he married the former Fannie Phelps of McCreary County, Kentucky. Ernest, born circa 1925, was their only child.

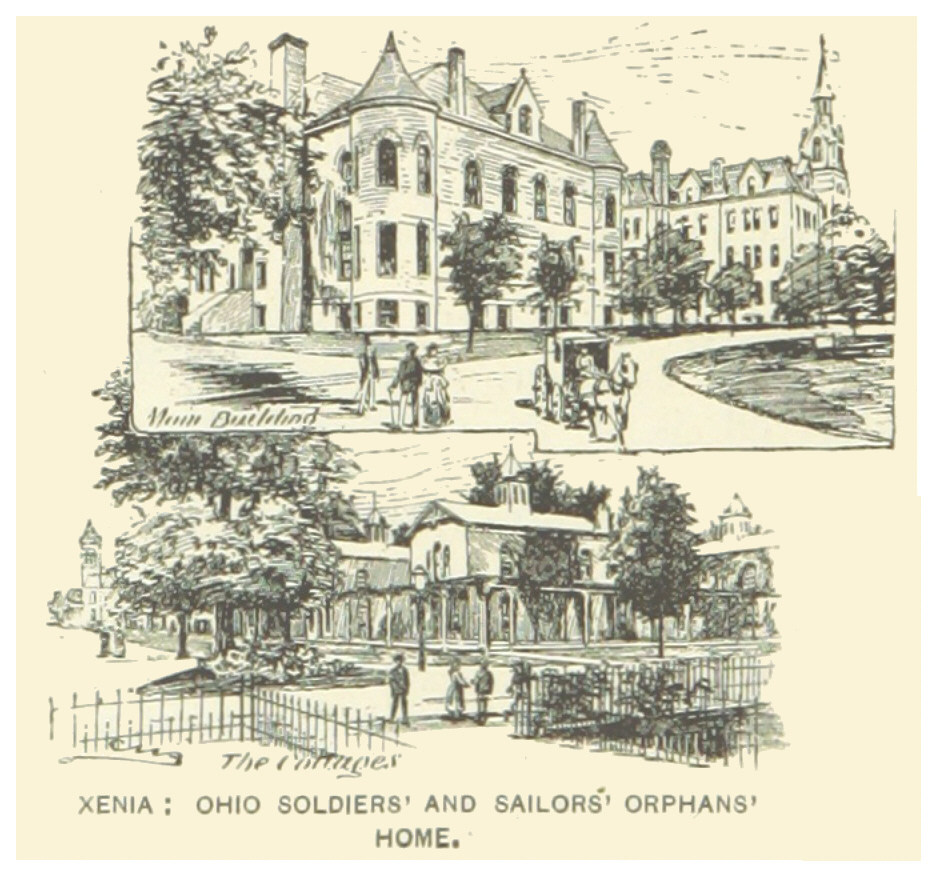

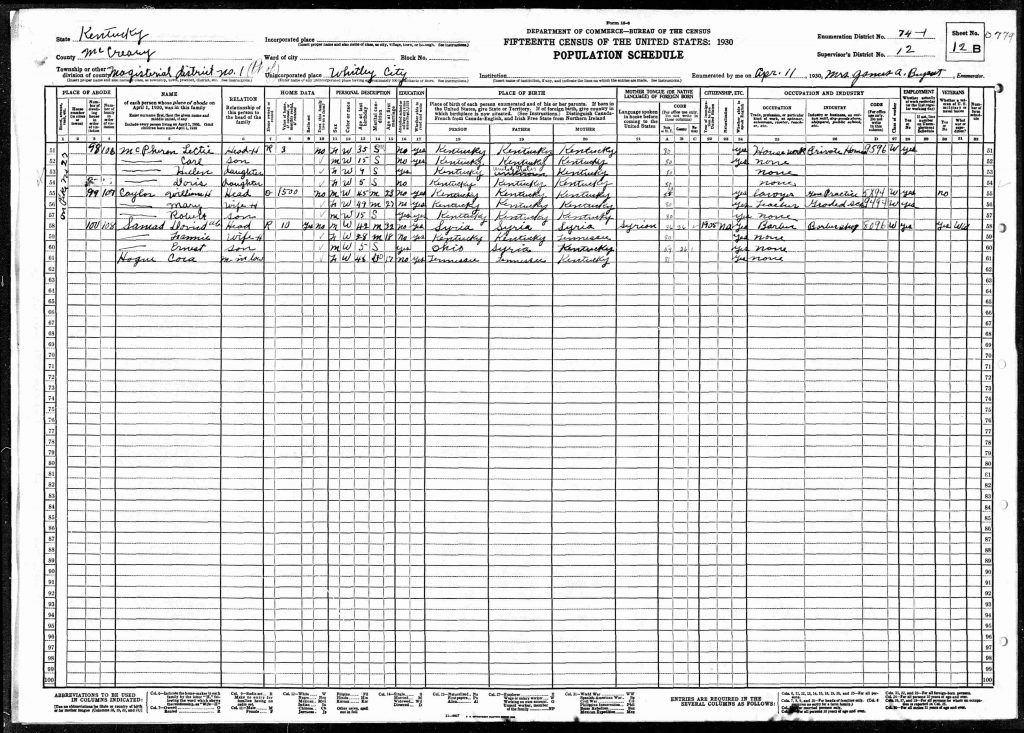

By 1930 the Sameds were living near Fannie’s family in Whitley City, Kentucky, in the southeast corner of the state, and David had resumed his career as a barber. After Fannie died of tuberculosis in 1931, David and Ernest moved to the Old Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Orphans’ Home in Xenia, Ohio. Ernest enlisted in Cincinnati in November 1941. Whether he was still living in Xenia at the time is unknown.

Edward Pitta’s great-grandfather Amaro Pitta immigrated in 1906 from the island of Madeira, a Portuguese possession in the Atlantic about 460 miles off the coast of Morocco, and set himself up in the bar business on the present site of the Transamerica Pyramid in San Francisco, just in time to get burned out by the fire that destroyed much of the city following the earthquake that April. He then set up shop anew across the bay and widened the scope of his business activities to include hotel accommodations and prostitution in Oakland and asparagus farming on Bradford Island in the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, about 35 miles to the east.

Edward Anthony Pitta was born in Oakland in 1925. The family business operations there being less than entirely legal, and his parents’ marriage having come unglued, it was thought that Bradford Island might offer him a more wholesome environment to grow up in. The island itself might have, but the water surrounding it and the world at large remained hazardous. There was no bridge to the island. You took a boat to and from it, or swam. Edward often did swim, and became, as his son James put it, “just a strong strong strong swimmer.”

But as crucial as his proficiency that way would prove in the war, it was of little use in his uncle’s brothel in Stockton one day when one of his uncle’s two girlfriends came in intending to shoot his uncle and shot Edward instead.

Having survived that mishap, Edward Pitta enlisted in San Francisco on 12 June 1943, one month before the Macaw was commissioned back across the bay in Oakland. The sailor and the ship would cross paths again eight months later.

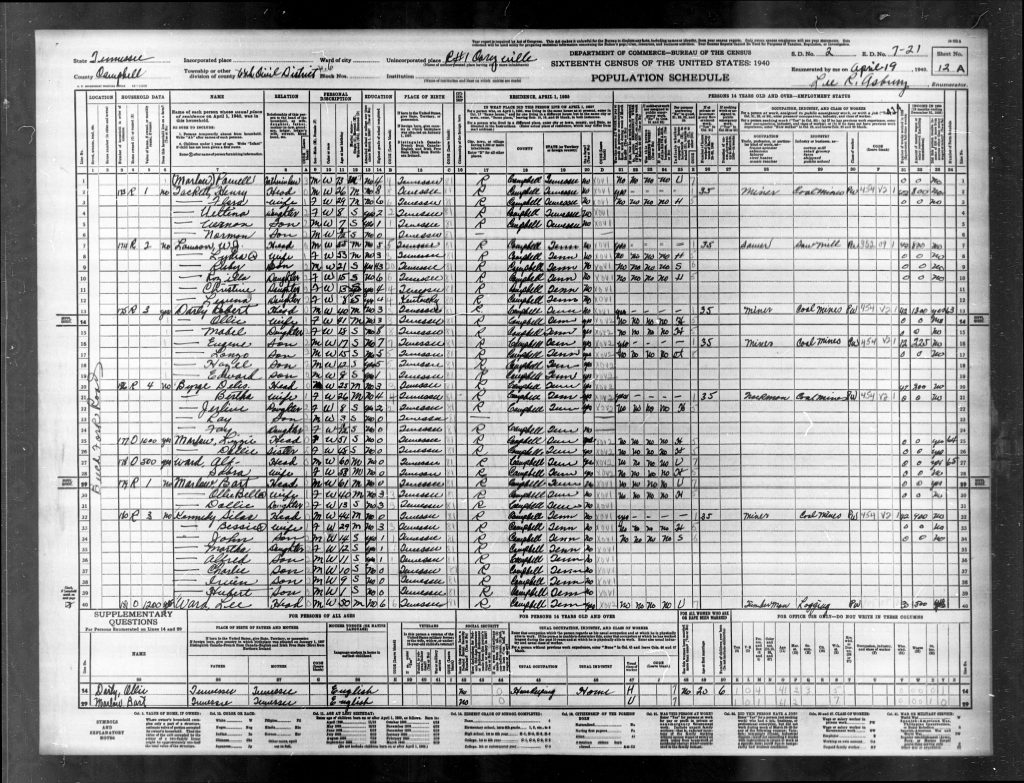

Eugene Daugherty (he went by his middle name) was one of five children in a coal-mining family from Cary, Tennessee, in the mountainous northeastern corner of the state about thirty miles from Ernest Samed’s boyhood home in Kentucky. Having dropped out of junior high school, Eugene followed his father into the mines as a teenager — according to the 1940 census, he worked twelve weeks in 1939 and made $225—then enlisted in Nashville on 17 October 1942. His brother Lonzo served in the navy during the war too. Lonzo apparently had little choice in the matter. According to family lore, it was either that or do time for rape. Lonzo reportedly served in the North Atlantic.

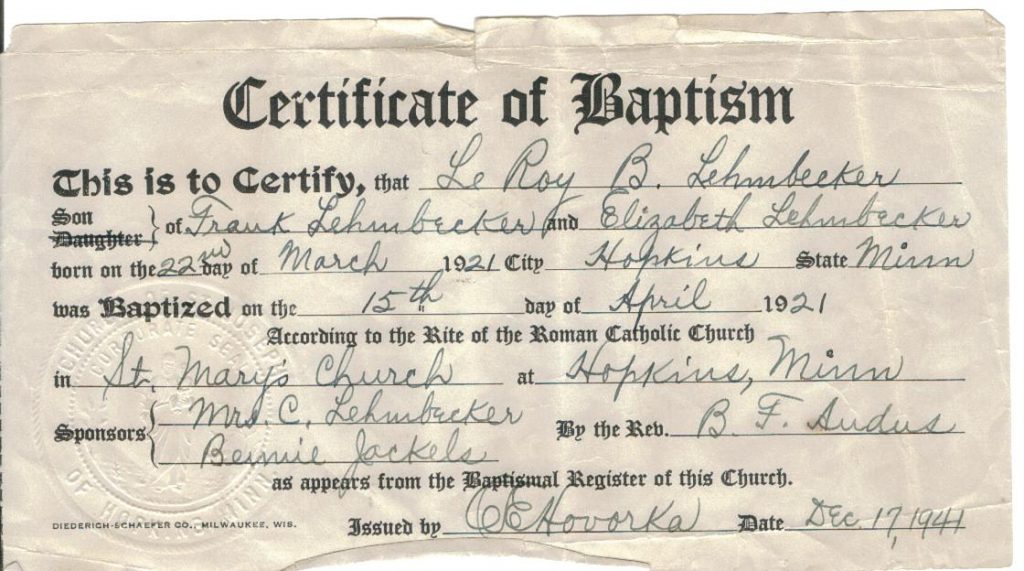

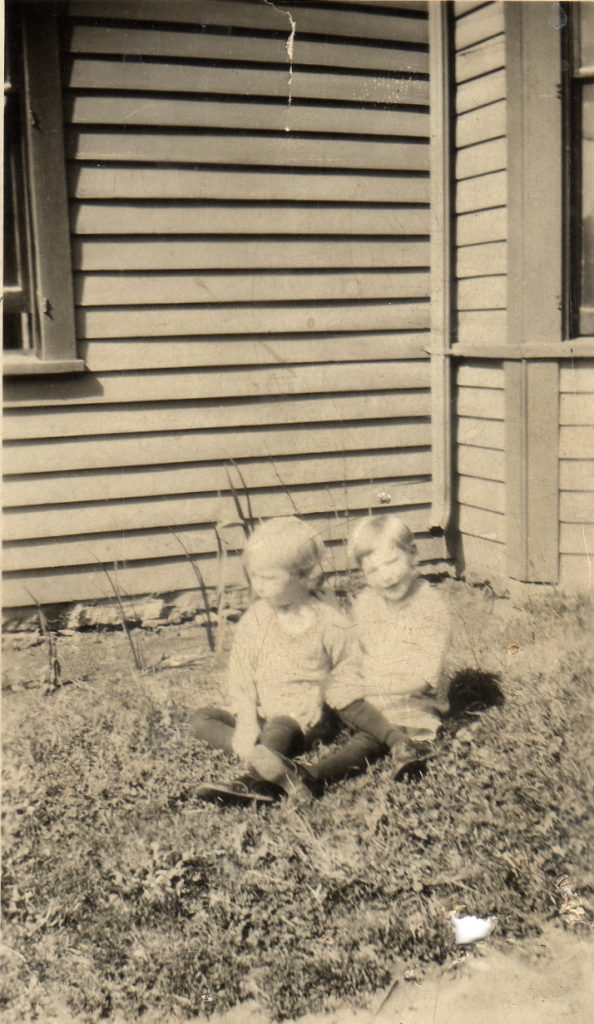

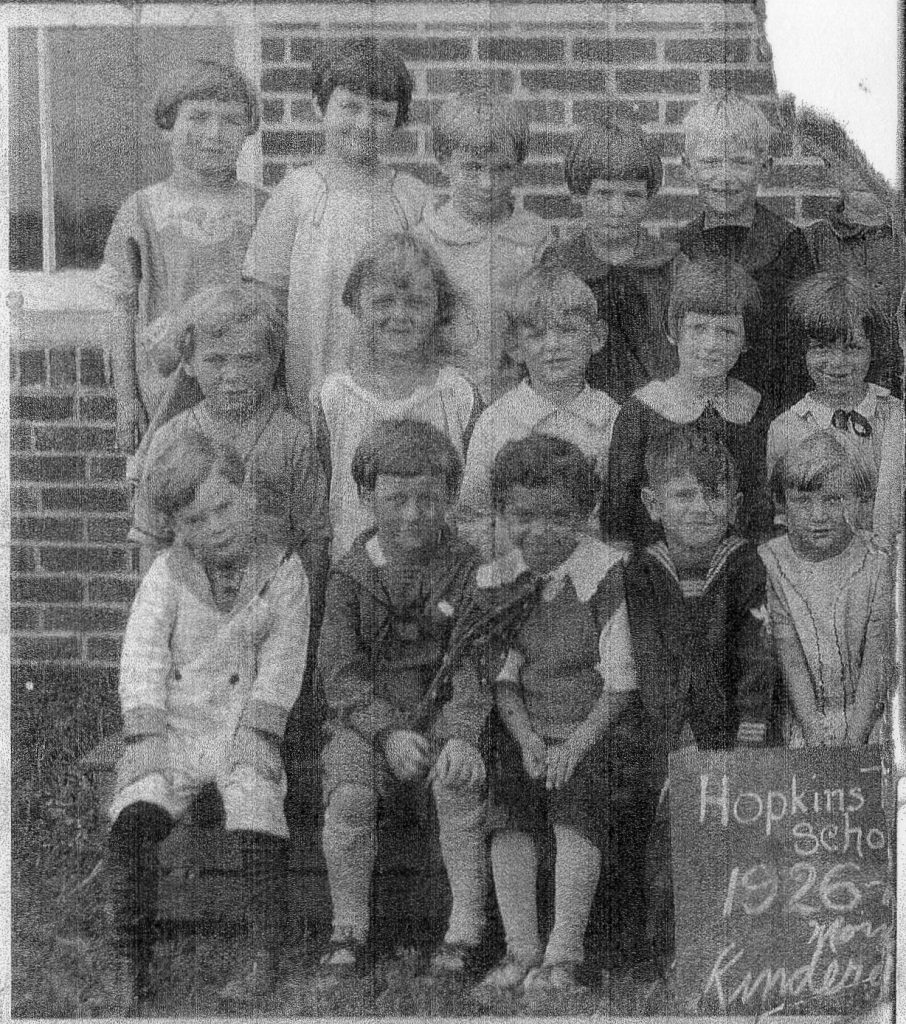

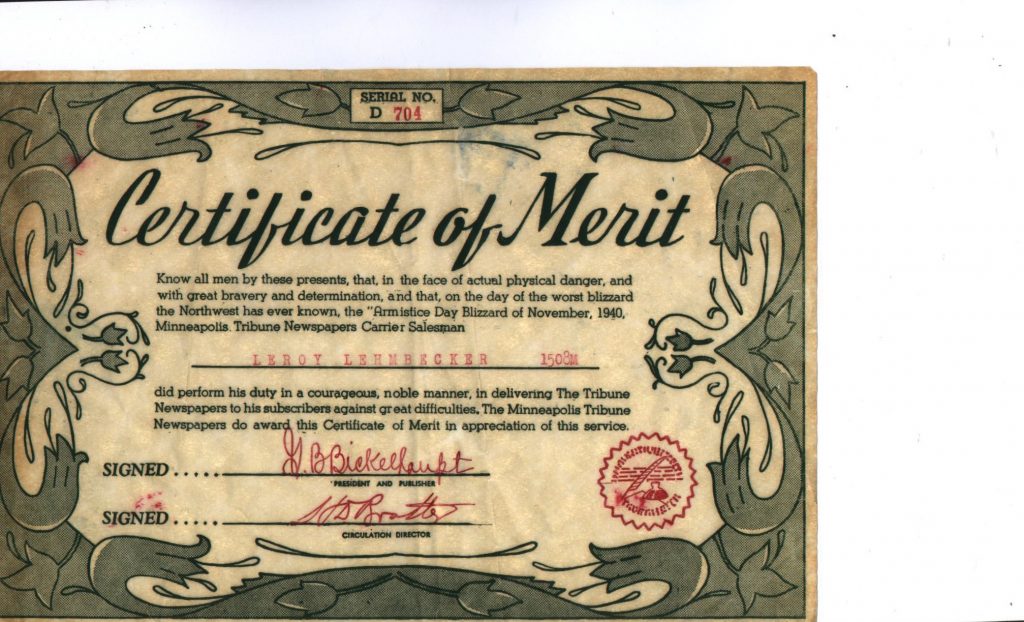

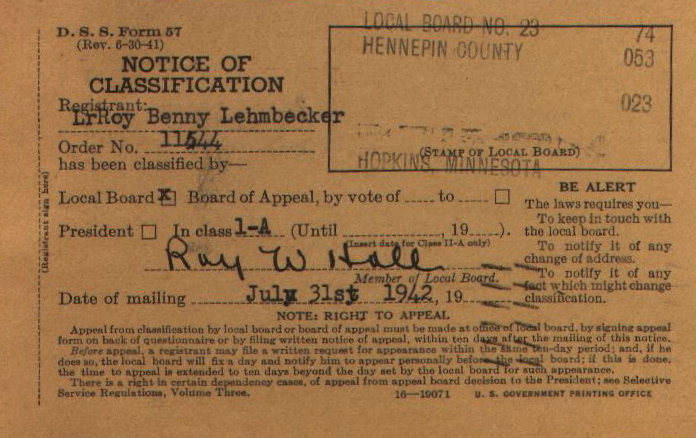

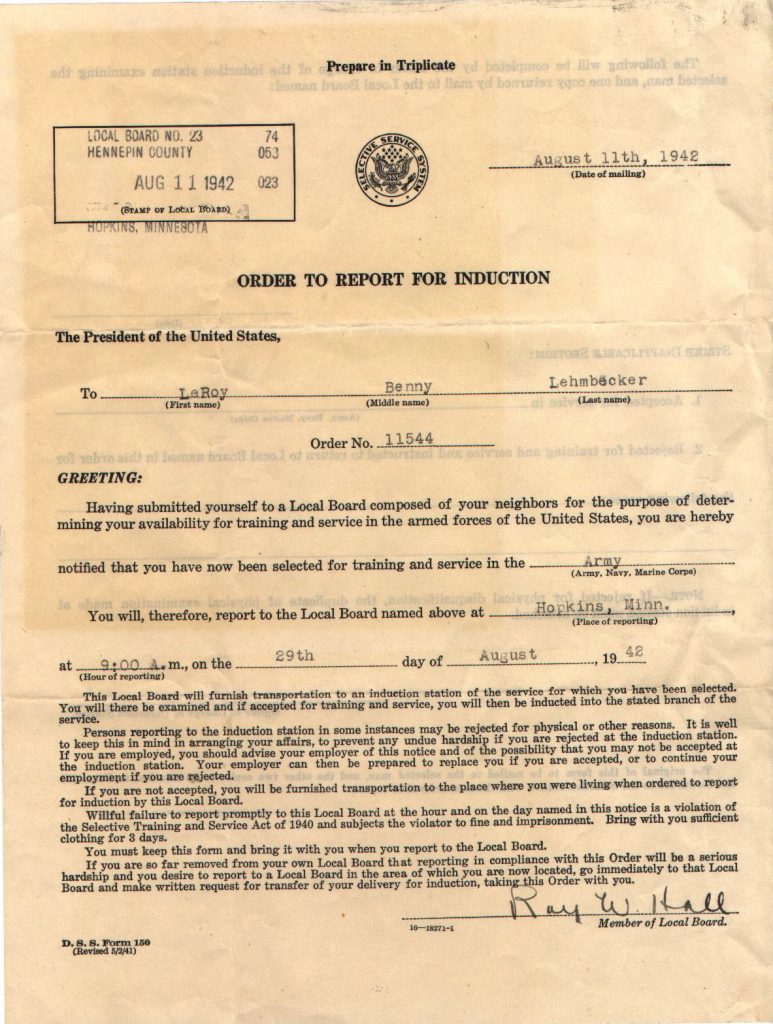

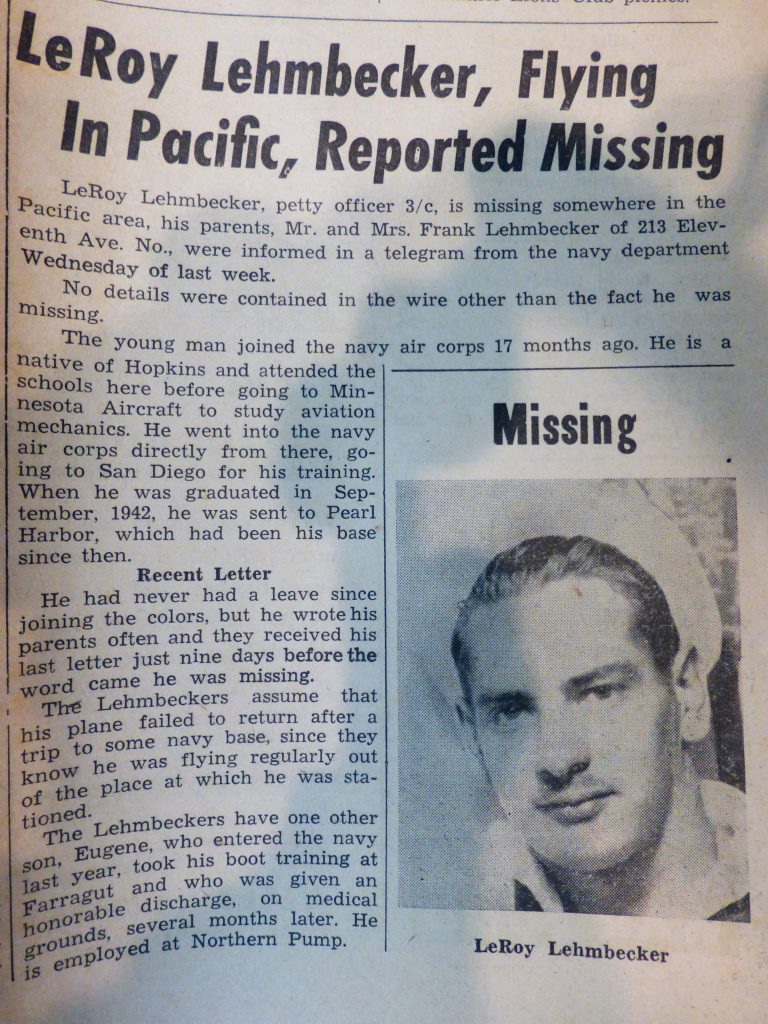

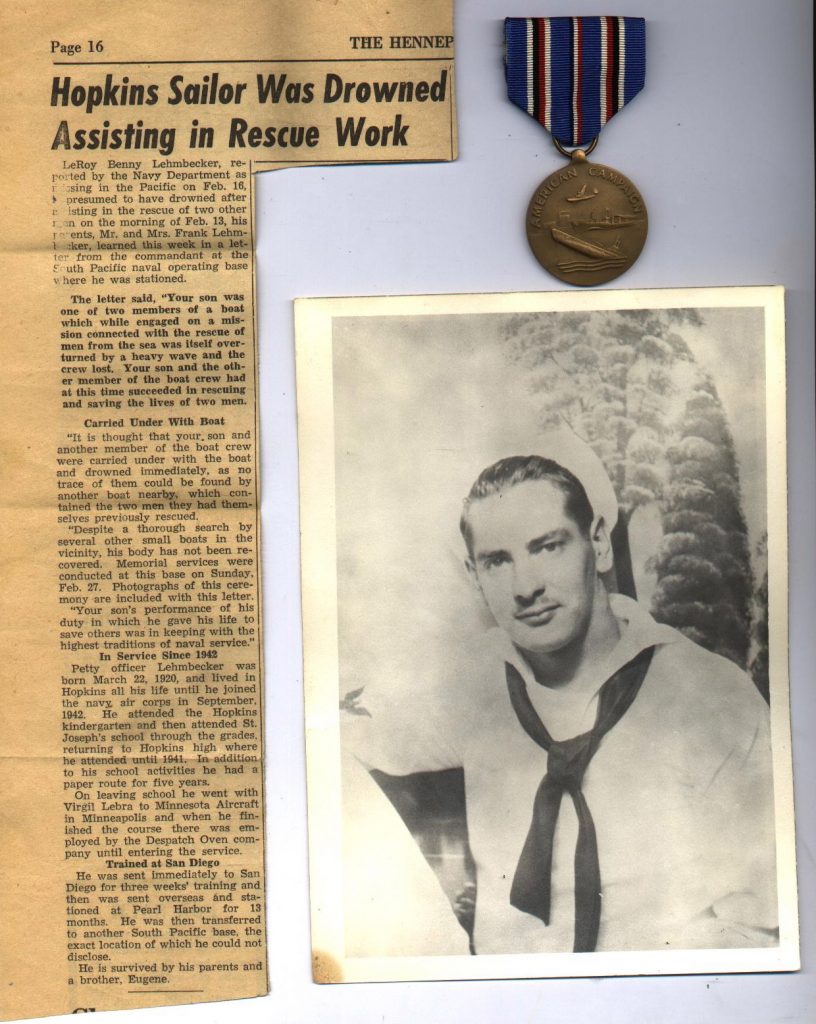

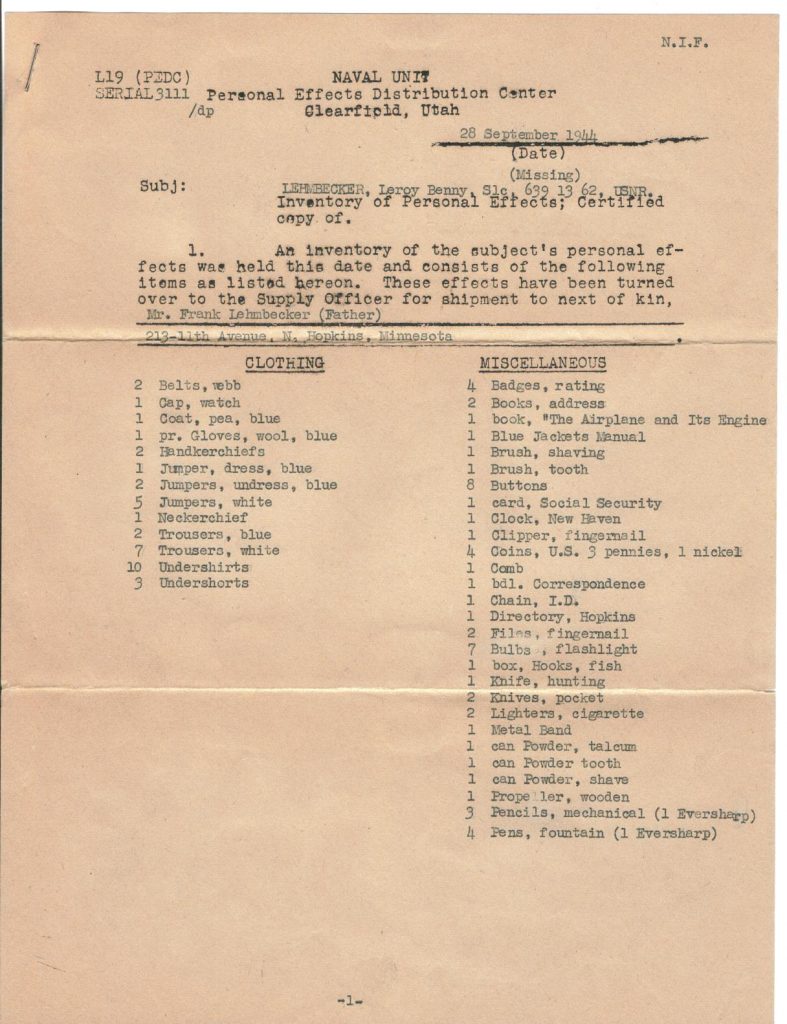

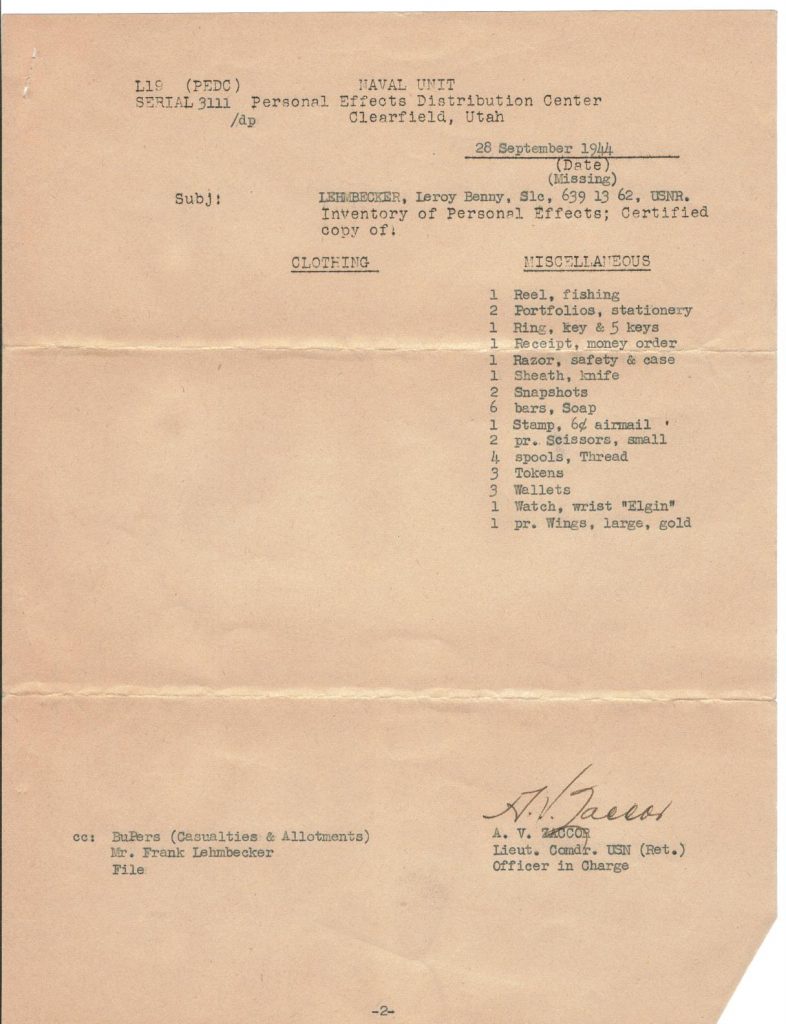

LeRoy Lehmbecker was from Hopkins, Minnesota, a suburb of Minneapolis, the older by about a year of two sons of a machinist for a farm implements firm and his wife. A hunting family, during the Depression the Lehmbeckers often supplemented their diet with blackbird. Standing just over five feet seven inches tall when he enlisted, LeRoy was nicknamed Pee Wee. He liked to tinker with radios. He delivered the Minneapolis Tribune for five years in his teens. The paper awarded him a certificate of merit for making his deliveries “in the face of actual physical danger, and with great bravery and determination” during the Armistice Day blizzard of 1940.

How actual the danger he faced that day was can be inferred from the historical record. That storm buried the upper Midwest in snow that drifted up to twenty feet deep. It left more than 150 Midwesterners and thousands of livestock dead, sank three ships on Lake Michigan, and all but wiped out commercial apple-growing in the state of Iowa.

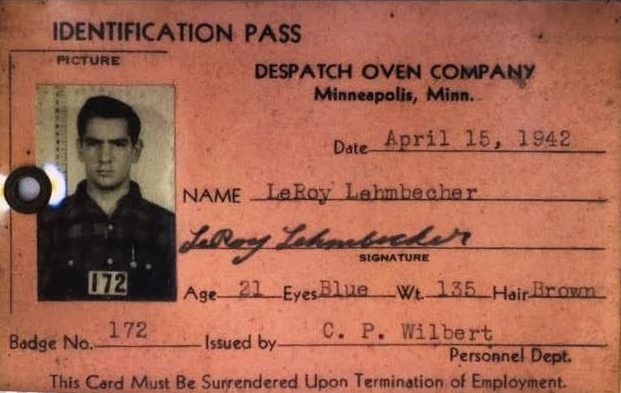

LeRoy attended Hopkins High School. Whether he graduated from it is unclear, but he did complete a course in aircraft sheet metal at the Minnesota Aircraft School in Minneapolis and won a commendation there for proficiency in riveting and assembly. In April 1942 he went to work for the Despatch Oven Company of Minneapolis, apparently as a truck driver.

By the time he enlisted four months later, he had taken a shine to fellow Hopkins resident Shirley Hutchenson, whose father owned and operated a feed supply store. They had had just one date, on which they had gone to a movie. She could not recall 64 years later what it was, but she had made a strong enough impression on LeRoy that in the one letter he proceeded to write her, more than a year after their one date, he told her he had a ring for her.

LeRoy trained at San Diego, spent fourteen months at the Pearl Harbor Naval Air Station, and transferred to NOB Midway in December 1943. He was 22.

In the predawn darkness of 13 February 1944, probably both rearming boats were engaged in carrying men and supplies over the troubled waters of the seaplane basin at the eastern end of Sand Island to eighteen PB2Y Coronado seaplanes that had spent the preceding two weeks making 2,100-mile-roundtrip bombing runs on Japanese-occupied Wake Island and were preparing to return to Kaneohe Bay Naval Air Station in Hawaii. By 0600 that morning, monitors in the Contractors’ Tower, a converted water tank that stood 170 to 200 feet high (accounts vary) at the back edge of the seaplane basin, reported men from the Macaw in the water on both sides of the reef.

A crash boat—a substantial craft designed with rescue operations in rough water in mind—was ordered to proceed out the channel and pick up whatever survivors it could without unduly putting itself at risk. Samed and Pitta in rearming boat No. 3 were ordered to check for survivors on Spit Island, a fifteen-acre scrap of sand on the edge of the channel about a half mile north of and inside the mouth. They were not to go any farther than that. The surf, even though it had subsided somewhat from its peak around midnight, was still far too big for rearming boats, which are smaller, open boats like rowboats, designed to operate on the comparatively tranquil waters that typically serve as anchorages for seaplanes.

Samed and Pitta ignored those instructions, proceeded straight to the Macaw, and capsized. Lehmbecker and Daugherty followed suit, receiving and ignoring basically identical instructions, going out to the Macaw and overturning, but not before picking up one man, Seaman 1/c George Washington Manning, and getting a line to another, Seaman 1/c Edward Wade. Manning and Wade survived. So did Edward Pitta. He drew on the swimming skills he had developed as a boy in the Delta in propelling himself a considerable distance—probably the half mile or so to Spit Island—against a stiff current up the channel to dry land.

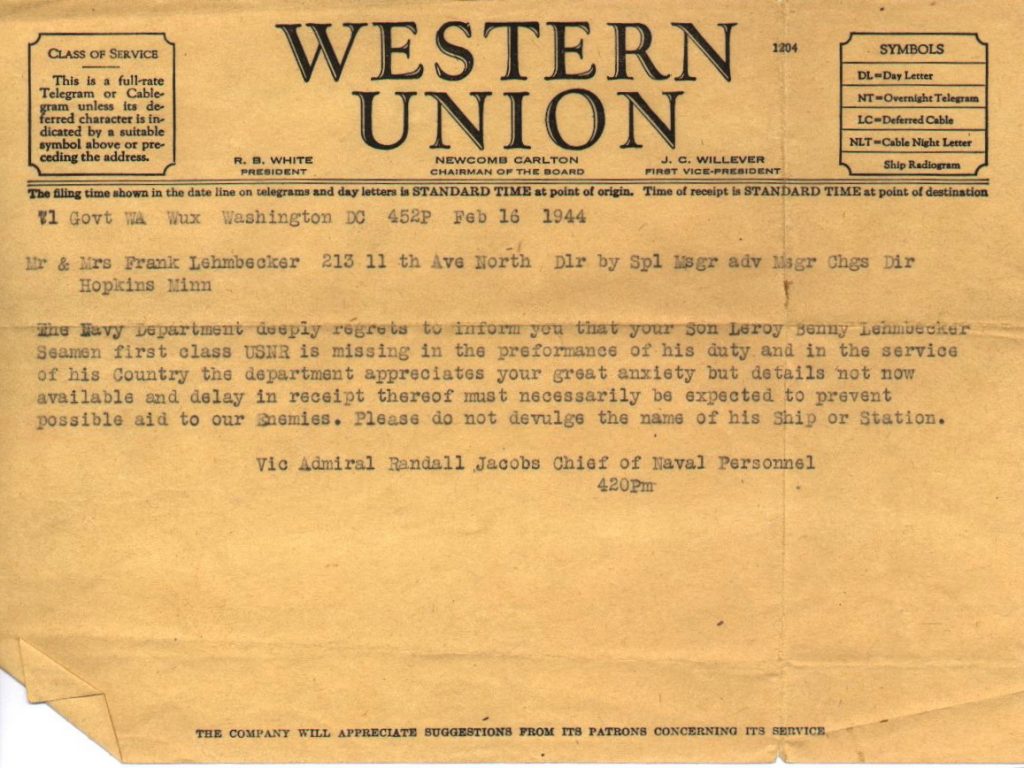

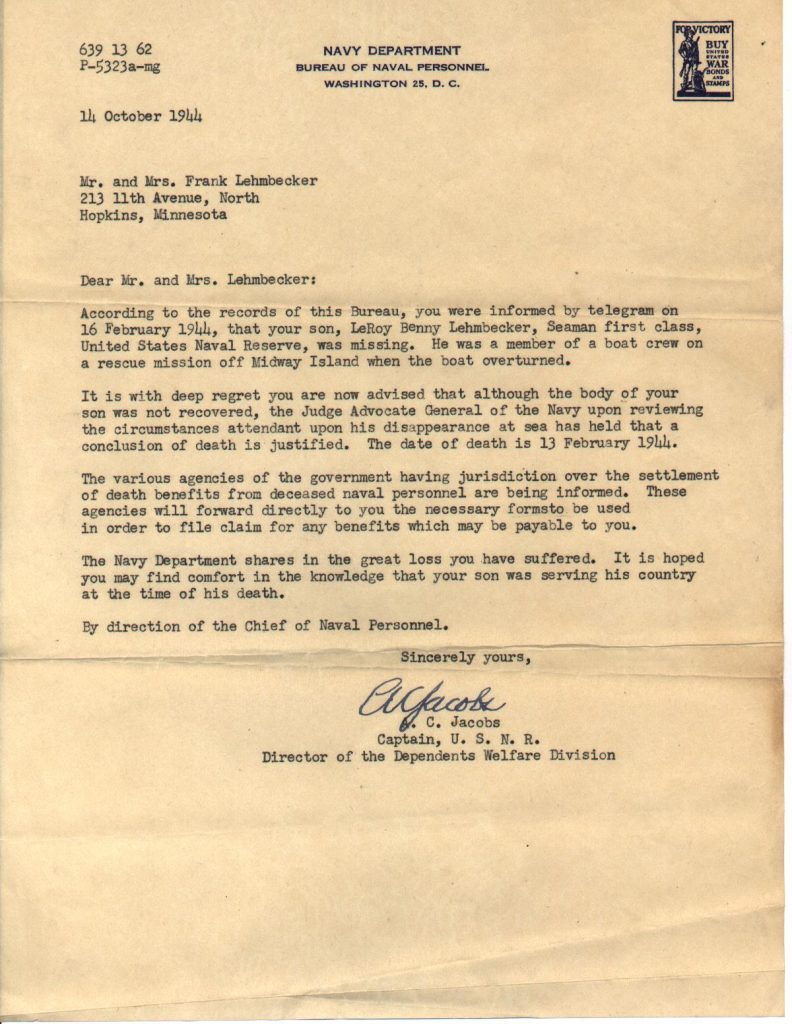

Eugene Daugherty’s body washed ashore four or five days later. He and Macaw crewman Robert Vaughn, a sixteen-year-old steward’s mate from Winston-Salem, North Carolina, were buried at sea on 18 February 1944. Ernest Samed and LeRoy Lehmbecker were never seen again.

Shirley Hutchenson said 62 years later that if LeRoy had brought her the ring he had told her he had for her, she probably would have accepted it. LeRoy’s mother refused for some time to accept word of his death. “My grandma always felt he’d be coming around the corner,” LeRoy’s nephew Gene Lehmbecker said. His disappearance left his parents bitter toward the Japanese. “If something was made in Japan, they just had a fit,” Gene said. “It couldn’t be in the house.” LeRoy’s death “basically just ruined their life.”

Ernest Samed’s father died in 1948, the probable beneficiary of a ten-thousand-dollar government-issued life insurance policy on his son.

Eugene Daugherty’s father, Robert Daugherty, lost both Eugene and Lonzo in the war. According to Robert’s daughter Vickie Cannon, Robert and the young woman Eugene had been dating before he enlisted came together in their grief. Robert’s first wife having died too, he and his son’s former girlfriend married and produced one child, Vickie, born in 1959, about 36 years after her half-brother Eugene was born and fifteen years after he died trying to rescue the men of the stricken Macaw.

Edward Pitta returned to California after the war and proceeded through a series of jobs—gas station attendant, factory worker, cannery worker, produce buyer, construction foreman, fisherman; lost at least two fingers in another ill-fated rescue attempt, trying to free a coworker’s arm from machinery in a rubber products factory; and survived another shooting, this by one of his six wives at their home in Fort Bragg in 1977. He and his wife both told the police that the shooting was accidental, like the one in the brothel in Stockton decades earlier, and no charges were pressed. Pitta died in November 2009 at the age of 86.

Photo gallery

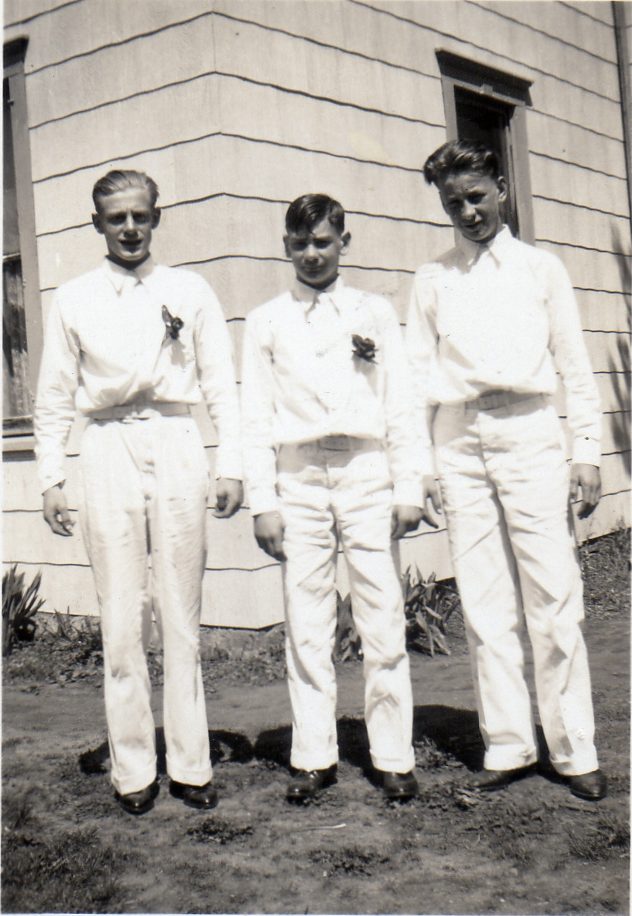

A fire years ago destroyed many of the Daugherty family’s photos. I’m hoping to get one of Eugene but haven’t received it yet. Photos of Edward Pitta are in short supply too, so most of what appears below features Ernest Samed or LeRoy Lehmbecker. Anyone having any photo not shown here of any of the four of them is heartily encouraged to send it along. (All Samed and Lehmbecker images courtesy Gloria Samad and Gene and Pat Lehmbecker respectively unless otherwise noted.)

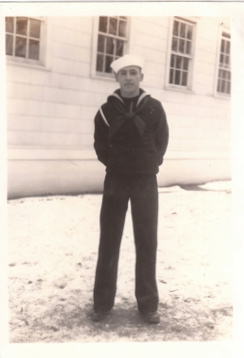

Lehmbecker

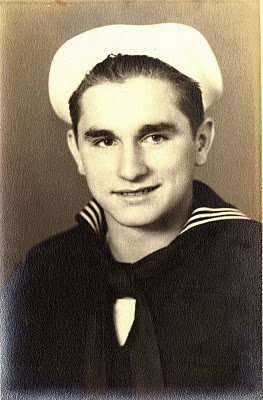

Samed

Daugherty