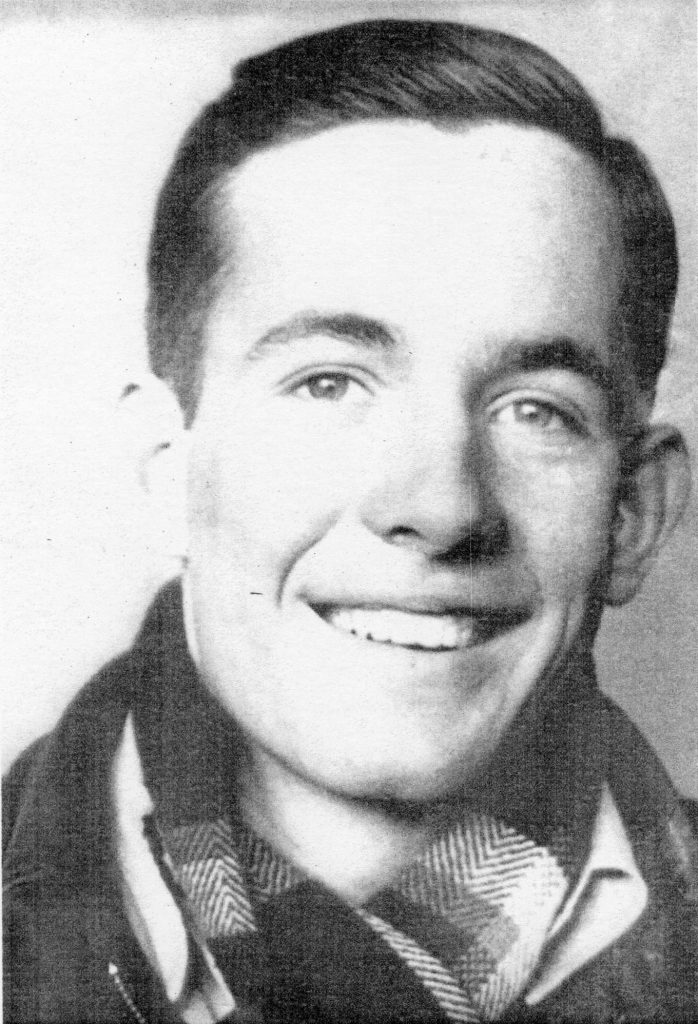

Reuben Embry Pickett was born March 16, 1925, in Ogden, Arkansas, the second of five children, four boys and a girl, born to James Layfette “Fate” Pickett, a prominent farmer in Little River County in the southwest corner of the state, and his wife, née Anne Embry. The Picketts, relatives of George Edward Pickett, the Confederate general whose troops made the fateful frontal assault on the Union line at Gettysburg, settled in that corner of Arkansas as homesteaders after the Civil War. Fate was born ca. 1870. He grew up in Ashdown, the county seat, one of seven siblings, four boys and three girls.

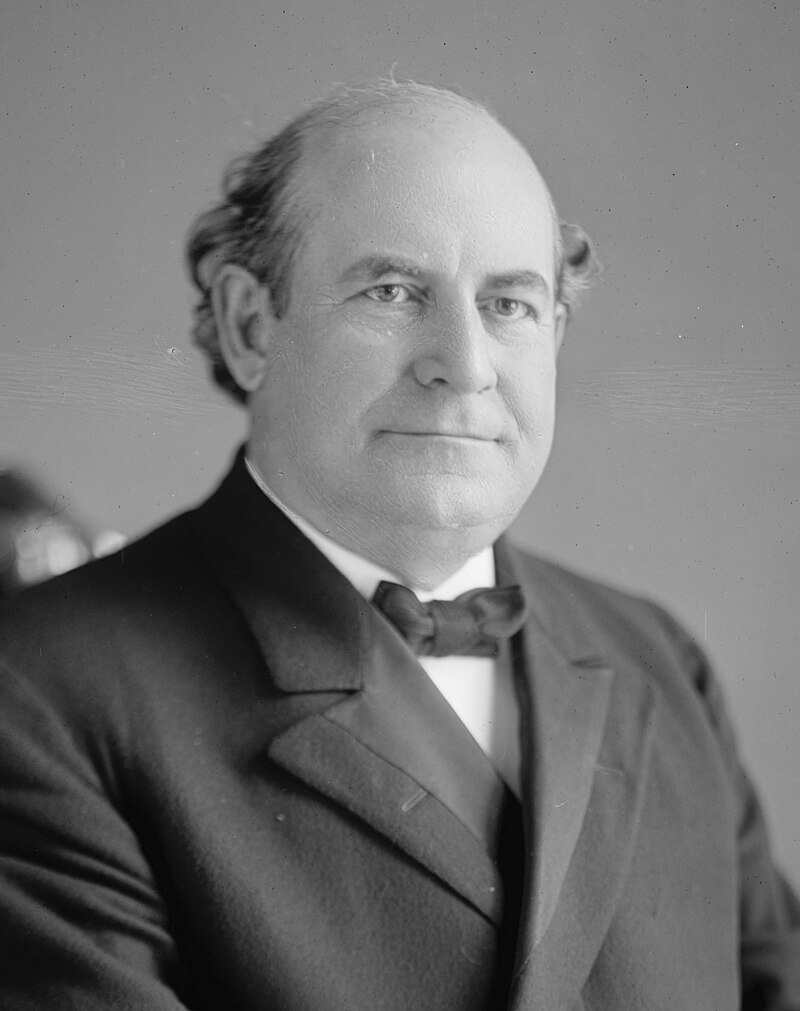

When Anne met Fate, he was considered the most eligible single man in Little River County. He sang, called square dances, and took an active role in local politics. He was always debating and politicking. He had a car, a prized buggy, and two fine matched bays, Dot and Daisy, he had gotten at a racetrack in Florida. He once debated three-time Democratic presidential candidate and prosecuting attorney in the Scopes Monkey Trial William Jennings Bryan in Galveston, Texas, on the subject of “the security of the believer” and won.

Fate married Anne Embry in 1920. He had three farms in Little River County, in Ogden, Millwood and Pine Prairie, and circulated his family among them as he and his two overseers decided which of the three was most in need of his attention. Black sharecroppers lived and worked on each of the farms.

Ashdown had two banks. Fate was considered the most successful farmer in the county. When the Depression hit and depositors started making runs on banks, the local bankers and town leaders sent a man to their house (the Picketts had no phone) saying they had to talk to him. They asked him to make the rounds of the county and persuade the other farmers, with whom he had more pull than anyone else, to sit tight and leave their money on deposit so the local banks could stay open. He told his wife he felt he should take both Dot and Daisy because he’d be doing some hard riding, going fast, and the two of them could spell each other. It took him two or three days to make the whole circuit. Some of the farmers took some talking to, but he got a lot of promises that there would be no run. When he got back home, Anne was crying. She told him both banks in town had closed.

Both Fate and his neighbors lost their savings. His were wiped out.

“He felt like they had used him,” his daughter, Beth Boone, said. “It broke him.”

According to Beth, Fate’s neighbors never blamed him for the loss of their savings—they knew he was in the same boat, after all. But the role he felt he had played—or, as he suspected afterward, that he had been tricked into playing—in cutting them off from their funds weighed heavily on him. He felt, she said, that the men on whose behalf he had made his ride had pressed him into service not with an eye to keeping the banks open, but to getting him out of the way while they proceeded with a plan to close them. “He felt like they had used him,” Beth said. “It broke him.”

In a subsequent conversation, Beth expressed sympathy for the bankers. Everyone was under duress at the time, she said, bankers included. But they weren’t the recipients of a lot of sympathy at the time. The banks were privately owned, so, Beth thought, the people running them had access to funds even after they closed. “That’s why nobody fussed too much when Pretty Boy Floyd went around robbing banks.” Floyd robbed a bank in nearby Mena. Bonnie and Clyde came to Texarkana, which was even closer. The farmers did not shed tears for the bankers.

Fate went to his bank (apparently it was not entirely closed) and received approval for a loan to pay taxes, buy seed, and help the families who lived on his land. But about a year later he was walking the floor crying. “I’d never seen my dad cry before,” Beth said. He told Anne the crops would have to rot in the field, there was no market for them. He told her: “What have I done to you? I thought I could just fill your hands with the beautiful life.” He told the sharecropper families on his farms he couldn’t support them anymore. In fact, he could no longer support his own family. “It killed him,” Beth said, “it just really did.”

“Even when the crops were rotting in the fields, he’d just go out there and walk the rows”—a habit she thought led to his contracting the pneumonia he died of in 1931. He was 61.

They were living in Pine Prairie at the time. His funeral was in the morning. That same day a delegation of bank and tax people came to their home to press claims on his debt and tax arrears. They took everything: all three farms, all the equipment and all the animals, including Dot and Daisy. The family had half a dozen insurance policies, but they found that only one of the issuing companies hadn’t also failed.

Faced with having to go back to work, Anne, a former school teacher, went off to Texas to renew her teaching certificate, leaving Reuben and Beth and their three brothers in Mountain Pine, a lumber company town about fifty miles southwest of Little Rock, in the care of an aunt with an authoritarian streak. Every year just before school started in the fall, a road crew would gravel the highway that ran past their home. The Pickett children were in the habit of gathering gravel from the road and making designs with it in their yard. Their mother indulged them in this creative larceny, but their aunt forbade it. John, the youngest, a toddler at the time, failing to understand her prohibition, proceeded to violate it, importing gravel in the customary way, and got a reprimand and a swat. Reuben responded by taking his brother in tow, marching onto the road and sitting in the middle of it with his baby brother between his legs and his hands on his hips. Aunt Hattie got the message. She never swatted John again.

Even at that age, Reuben combined strong principles with level-headed pragmatism. By age five he had gotten in the habit of climbing a tree in the family orchard and eating green apples—a habit he persisted in despite the fact it gave him abdominal distress. His mother told him if he did it again, she’d have to switch him with a switch from the peach tree. He did it again. She had him cut a switch. His siblings protested on his behalf. His mother said if he would promise not to repeat the crime, she would withhold punishment. Reuben thought about it, according to Beth, and said, “Momma, I may just wanna do it again, so go ahead.”

His practical approach to things got a public airing of sorts about eight years later, in 1939, in an English class he and Beth were in together. (Beth was one grade ahead of Reuben, but at their little school two grade levels were sometimes assigned to the same class. She said she thought she was a sophomore and Reuben a freshman in high school at the time.) They had an assignment to write a story containing a beginning, a crisis, a resolution, and exactly 100 words. Beth applied herself assiduously to the task. Reuben seemed to be neglecting it. The stories were due on Monday. On Sunday night, Beth asked Reuben if he hadn’t better hurry up and write his. He replied that he had just finished it. On Monday as she collected the stories, their teacher announced that she would be selecting some of them to be read in front of the class. On Tuesday she called on Reuben. He stood and read: “I had a cat. My cat got hungry. I fixed the food. I called, “Kitty, kitty, kitty, kitty, kitty …” After he called the cat about eighty times, it showed up and ate its food, to the tune of exactly 100 words. Their teacher, like Reuben, had a sense of humor. His presentation left her with her head on her desk, convulsing in laughter.

When Reuben was about 14, he got a summer job as a clerk in the grocery section of the general store in Mountain Pine. As the school year approached, he asked whether he could shift to delivering groceries—he wanted to drive the delivery truck, and that job wouldn’t interfere with his school schedule. There was a white section of town and a black section. Reuben delivered to both. The other delivery boys, Beth said, would put the black customers’ groceries by the side of the road and honk. Reuben would carry their groceries inside and ask where they wanted them, where the potatoes went, whether they wanted the flour in the flour bin. If they did, he put it there. He always had time to stay and have a piece of pie.

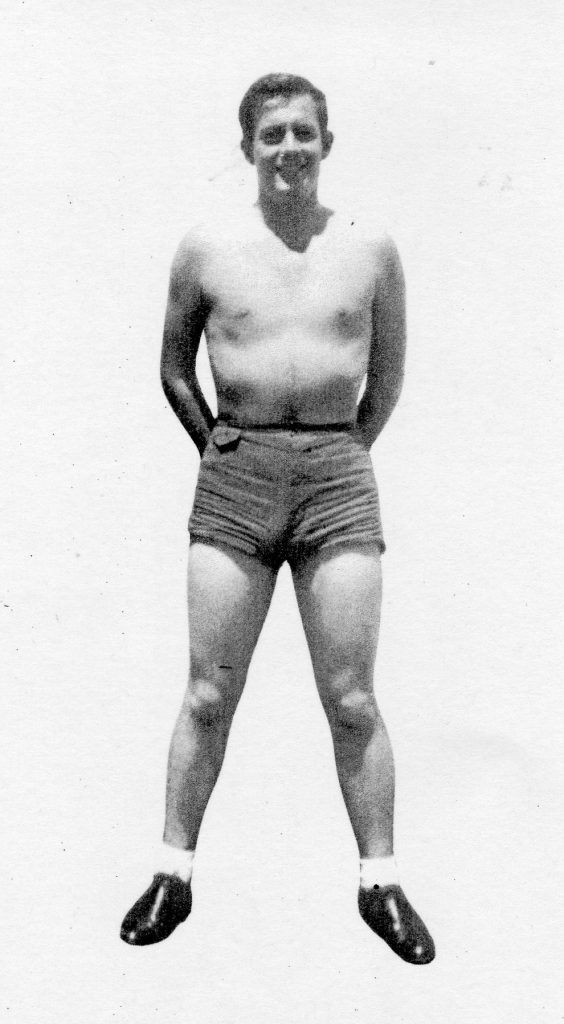

Reuben enlisted in the Navy at age 17 in 1943 after graduating that year from high school, during which he played basketball and starred in boxing and wrestling. He wanted to be in the Navy — specifically, in submarines — and he had a sense that the officer at the recruiting station would deny him his choice. He told Beth later, “I looked at him and I knew, whatever I said, I wasn’t going to get it”—so when the recruiter asked him what branch he wanted, Reuben said the Army, and the recruiter said, “Well, you’re in the Navy.”

Reuben served during the war as a radioman aboard the submarine USS Snapper (SS-185). The Snapper and the Macaw may have literally been two ships passing in the night in early January 1944.

The Snapper, having undergone a refit following its eighth war patrol, departed Midway for Pearl Harbor on January 7. The Macaw arrived at Midway from Pearl Harbor the next day. During the four weeks the Macaw spent aground on the reef at Midway, the Snapper was undergoing an overhaul at Pearl Harbor. The Snapper returned to Midway on March 13, one month after the Macaw sank. It may have been the forlorn sight of its mast projecting at an angle from the water at the mouth of the channel into the lagoon that day that inspired Pickett to write his poem about the Macaw.

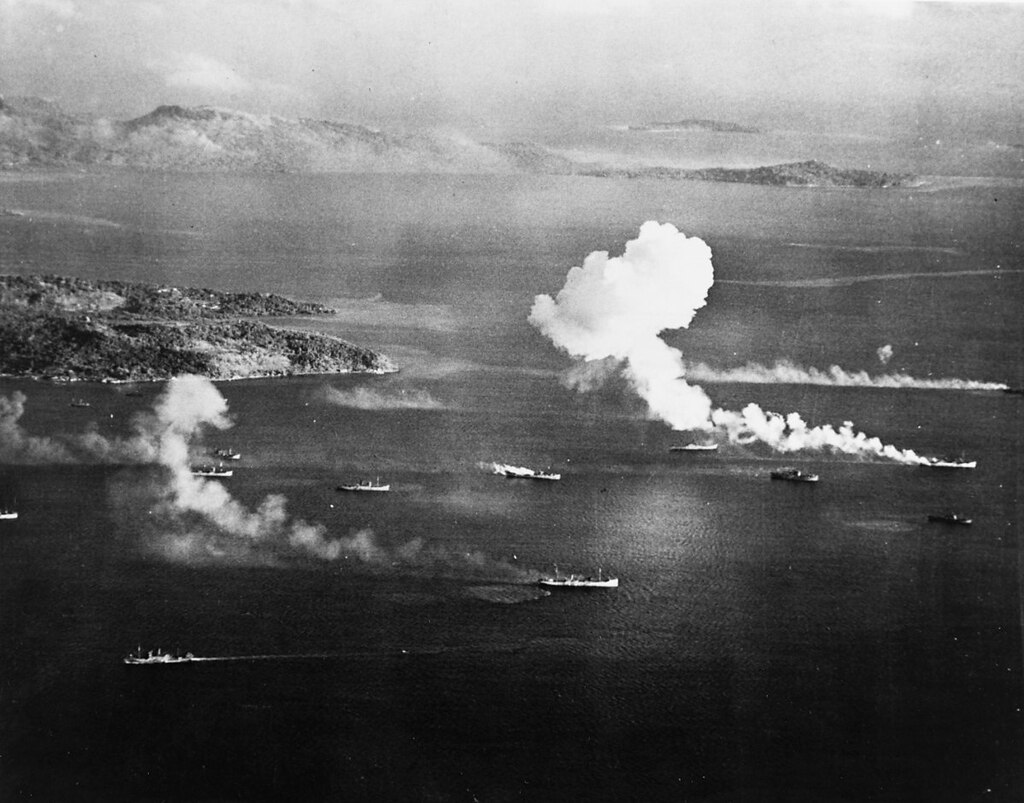

Among his duties on the Snapper was manning a deck gun in surface combat, and the Snapper saw some while Reuben served aboard it. The Snapper was on lifeguard duty on 9 June 1944, off Truk Atoll in the Carolines, standing by to pick up downed American fliers during an aerial bombardment of Japan’s main forward naval base when a Japanese plane bombed the sub, killing one crewman and injuring several others, including the captain.

Reuben came home on leave just once. There were lots of proposals for parties in his honor, and he rejected every one. He told his mother and sister a time had come when he knew his time was up. He said he had asked God to please let him live long enough to go home and tell his family it was all right. Then, he said, he could die at peace. He said he’d come home to tell his family how much he loved them and to spend every second he had with them, not to get lionized at parties.

As he was about to board his plane to return to the Snapper, he took his ticket out of its envelope, handed the envelope to his mother, and said, “Momma, you might need this. Hang on to it.”

Beth told me his flight number was printed on the envelope. In fact there were probably at least two flight numbers on that envelope, the latter (or last) being American Airlines flight number 6001, “The Sun Country Special,” which departed New York’s La Guardia Airport at 7:23 pm EST on January 9, 1945, en route to Burbank, just northwest of Los Angeles, with stopovers in Washington, DC, Cincinnati, Memphis, Dallas, El Paso and Phoenix. Reuben probably boarded it in Dallas. The plane, a Douglas DC-3, had a crew of three—the pilot, Capt. Joseph Russell McCauley, First Officer Robert Gaylord Eitner, and a stewardess, Lila Agnes Docken. On its last leg it carried twenty-one passengers, all service members, including seventeen soldiers and four sailors.

After the plane left Phoenix, foggy conditions at Burbank prompted a brief change in the flight plan, with clearance to a neighboring airport, but at 3:06 a.m. PST Los Angeles Flight Control recleared the plane for landing at Burbank. An hour later it made its approach there, passed overhead, banked off to the left, and vanished into the fog.

At 4:07 the pilot, Capt. Joseph Russell McCauley, radioed that he was unable to maintain visual contact with the ground and was diverting to Palmdale. Subsequent attempts to contact him by radio failed. The wreckage of the plane was found later that day in McClure Canyon, about three miles north of the airport. There were no survivors.

When Reuben’s family heard on the radio that an American Airlines flight had crashed into a mountain outside Burbank, they called the airline and found that the number (or one of the numbers) on the envelope matched that of the plane that had crashed. They held out hope for a few days that an officer might have pulled rank on Reuben and had him bumped from the flight to take his seat when the flight was officially militarized at a stopover, but it wasn’t so. The bad news was confirmed. Reuben was dead.

The mill in town published a newspaper. A photo of Reuben appeared in the paper with the story announcing his death. Early the morning after the story ran, his mother and sister awoke to find their house surrounded by black people. His mother went to the gate and invited them in. Some if not all of them Reuben had delivered groceries to. Among them was a minister who asked to come into the yard and speak for the whole assemblage. Inside the front door of the home of every black family in town, he said, was a table. On the table was a Bible, and on the wall above the table was a picture of Joe Louis. He said everyone congregated there that morning had agreed to go home, cut Reuben’s picture from the paper and put it on the wall next to Joe Louis.

A woman asked permission to come into the yard and speak. She was in the habit of giving her daughter a list and sending her to Reuben’s store for groceries. A group of white boys would hide by a railroad trestle she had to cross en route to the store and back and harass her. Reuben was the local high school boxing and wrestling champion. When he heard about the harassment, he told the woman to send her daughter to the store late in the day when he would be there and said, “I’ll walk her home.” He did. Her mother said, “Those boys never dared bother my daughter again.”

This all came as a revelation to Beth and her mother. “We had no idea he had that relationship” with the black people in town, Beth said.

Reuben Embry Pickett died 10 January 1945. He was 19. His brothers James and Fred also served aboard submarines during the war. Both survived it. All four of Reuben’s siblings lived into their eighties. The Pickett family remains a presence in southwestern Arkansas.

Sources:

“American Airlines Flight 6001,” Wikipedia

“Aviation Safety,” asn.flightsafety.org/asndb/338871

Beth Boone, with whom I talked 20 March and 27 August 2011 and 9 October 2016.

Deadliest American Disasters and Large-Loss-of-Life Events, usdeadlyevents.com

“List of American Airlines Accidents and Incidents: American Airlines Flight 6001,” Wikipedia

“1945 Airplane Crash,” wescla