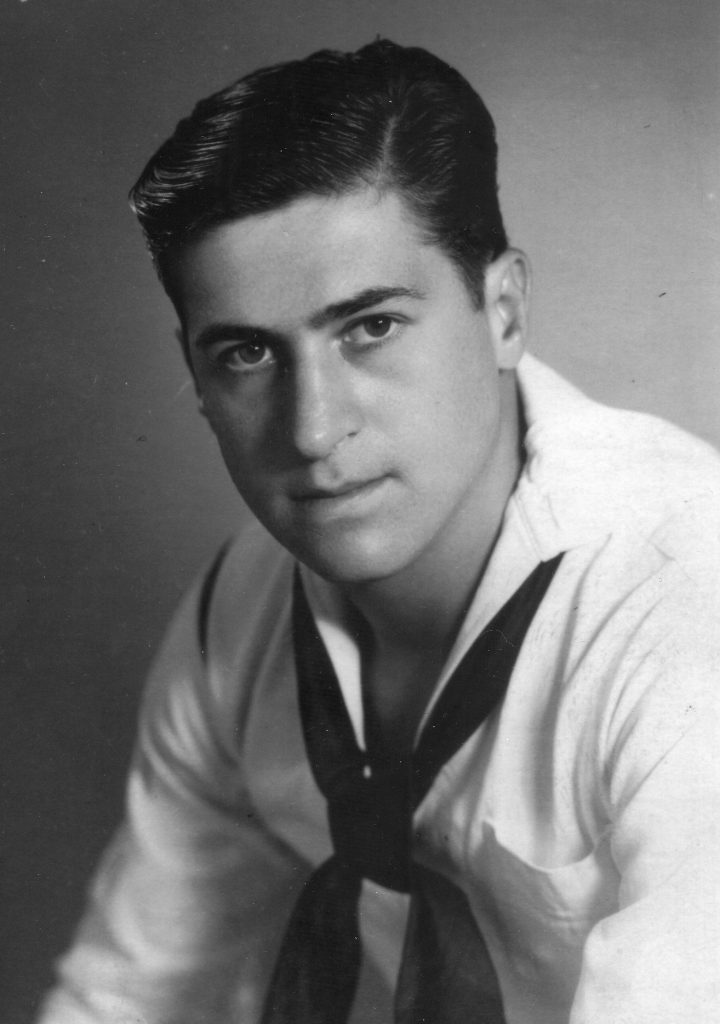

Albert F. Bolke was born May 6, 1923, in Chicago. He grew up there on the South Side.

His father was a steelworker, a native Chicagoan of Polish descent. Albert’s mother, Anna (maiden name Extejt), was the second of his three wives. He had two children by his first wife and eight more—four boys and four girls—with Anna, who was of Croatian descent, from Pittsburgh, and fifteen or sixteen years old when they got married. The two children of the first marriage lived elsewhere after their mother died.

The family Albert grew up in included just Anna’s eight children. Of the ten of them, children and parents, Albert was the only one with the name Bolke. For everyone else it was Bolka. His father was said to have been drunk when he filled out Albert’s birth papers and misspelled his own name.

Life in the Bolka/Bolke household was not easy. Albert’s father was an alcoholic. They moved a lot. They were in the habit of moving out the night before the rent was due. They didn’t have enough to eat. Albert was scrawny from malnutrition. They were poor. Family lore attributes Albert’s failure to graduate from high school to his being too busy as a child stealing coal to keep the family warm to go to school.

When Albert was ten, Anna died at age 33 in childbirth. She was taken in a patrol wagon to a hospital in downtown Chicago and died there. It was her tenth pregnancy—she had had one miscarriage. When she died, her last baby died too. Two weeks later, Albert’s father was married again, to a woman named Julia he had hired, poverty notwithstanding, to take care of the kids.

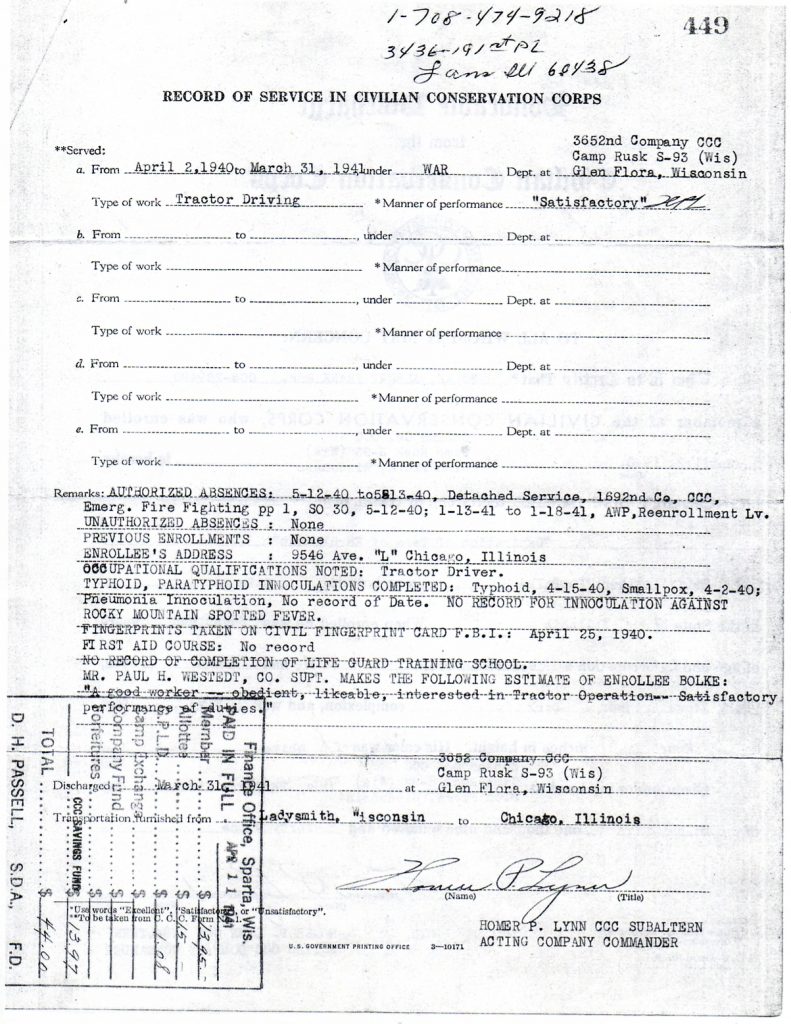

Albert and Julia did not get along. Albert would hide out at his aunt’s place when Julia called the cops on him, which she did repeatedly. One day he intervened when Julia was beating up one of his sisters. Julia tried to have him arrested. A policewoman investigated, figured out what was going on, and encouraged him to join the Civilian Conservation Corps, a Depression-era federal jobs program for unemployed, unmarried young men. He did. He spent a year, from April 1940 through March 1941, at Camp Rusk in tiny Glen Flora, Wisconsin, building roads and fighting at least one fire, then went to work back in Chicago for R. R. Donnelly, a paper company and publisher of phone books.

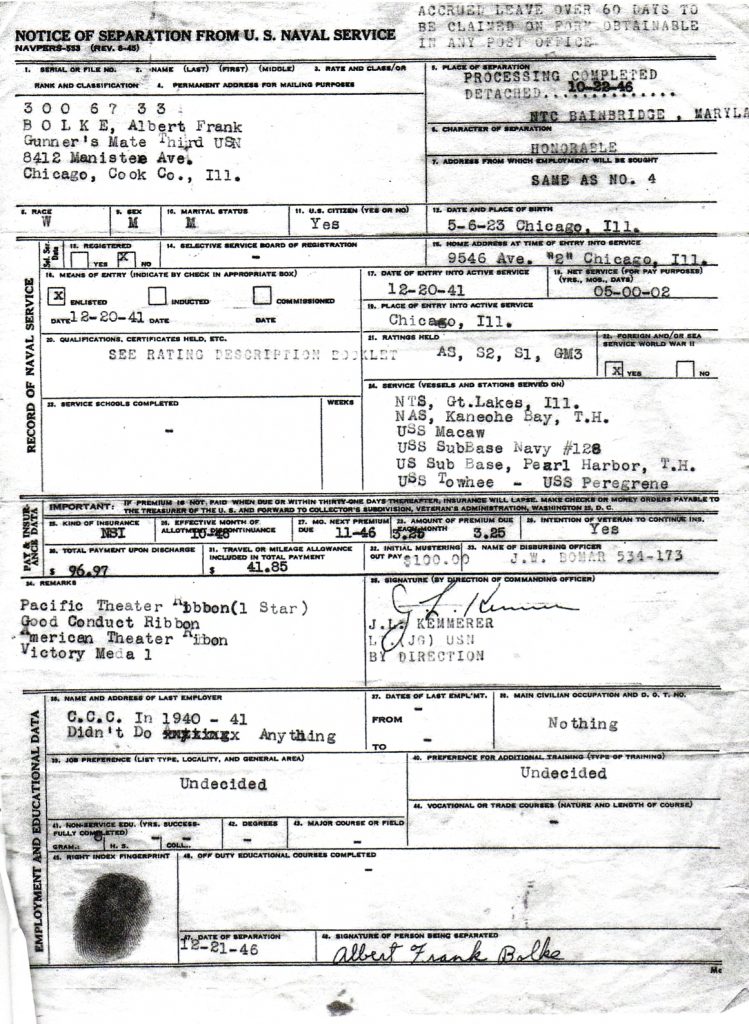

He spent a year and a half or so at R. R. Donnelly and hated it, largely on account of all the ink his job put him in close proximity to. Much of it ended up on him. The publishing industry having no hold on his affections, he was quick to enlist after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. They attacked on December 7. He enlisted the next day. His official enlistment date is December 20, but only because the initial processing took about two weeks. He signed up for six years.

His three brothers, Bill, Junior and Benny, all served in the Army.

Albert did his basic training at Great Lakes, on Lake Michigan north of Chicago, and got through it somehow despite the fact that he couldn’t swim. In the CCC and the Navy he ate better and started putting on weight. He boxed in the Navy. He claimed to be 5-9, a figure his family regards as modestly exaggerated. (In fact, it appears to have been greatly exaggerated. His CCC discharge form indicates his height as 5-4.)

Bolke was one of the 22 men aboard the Macaw the night it sank and, given his inability to swim, perhaps the unlikeliest of the seventeen survivors. By one account, when asked how he made it to shore, he said he hit bottom and just started walking. In fact he probably owed his survival to his life vest. After the Macaw, he served aboard the USS Towhee (AM-388) and the USS Peregrine (AM-373), both minesweepers.

He met his future wife, Martha (née Suszynski), while home on leave in December 1945 through the good offices of his sister Connie, who had a job at the time at one of Chicago’s two W. C. Ritchie & Co. box factories, where production had shifted during the war from containers for baby bottles to containers for shells. Martha was one of Connie’s coworkers. One day that month Connie told her, “You’ve got a date with my brother.”

Actually they had four dates, in four days. On their first date they went bowling. On their fourth they went to a Maureen O’Hara movie at the Avalon Theatre on East 79th Street (probably The Spanish Main, an adventure film set in the Caribbean in the 1700s starring O’Hara and Paul Henreid). That evening he said to her, “I’m shipping out tomorrow. Will you marry me?” She said yes.

The two of them had much in common. Both were born in Chicago in 1923 and grew up on the Southside in a family of four boys and four girls. Both of their fathers were steelworkers of Polish ancestry. Martha’s father was actually from Poland. He had immigrated as a teenager by himself, unaccompanied by relatives, as had his wife, Martha’s mother, who came from Germany and settled first in Hammond, Indiana. The two of them met at a wedding.

But for all their similarities, Albert and Martha apparently experienced childhood very differently. Martha’s recollections of hers seem basically positive. Among them was that of going to a bar across the street from her friend Sylvia Loferski’s home and buying five-cent cigars for the barber who rented a shop downstairs in Sylvia’s building, and pitchers of beer for 25 cents for Sylvia’s dad. Martha and Sylvia would bring a pitcher to the bar and get it filled.

After his fateful leave in 1945, the Navy sent Albert to Sasebo, Japan, then Hawaii, then Charleston, South Carolina, where he and Martha were married 6 July 1946 in St. Mary of the Annunciation Catholic Church. Albert made all the arrangements. There were a couple of witnesses. It was a Saturday. No one else was in the church. The priest declined Albert’s offer of payment, telling him something to the effect of “You’re a sailor, you’ll need that.” They were out the door in ten minutes. It was, in Martha’s words, the quickest and cheapest wedding ever—ten minutes and free.

For their honeymoon, they stayed two weeks at a boarding house in Charleston. As Martha said 67 years later, “Why go anywhere?” They were already in Charleston.

Afterward Martha went back to Chicago and Albert got assigned to Newport News, Virginia. He loved the Navy—he planned on making a career of it but reconsidered after he met Martha. The Navy gave men like him who had signed up for six years the option of mustering out after five. He did, on 3 December 1946.

Not long after their own wedding, they attended nuptial festivities back in Chicago for a friend of Martha’s at Bishops’ Tavern at 84th and Baltimore, owned and operated by the Biskupskis, who had Americanized their name in applying it to their business. Mrs. Biskupski was tending bar that day. When she overheard Al telling the story of being channeled into the CCC by the policewoman who handled the case when his stepmother tried to have him arrested, she identified herself as the policewoman. Martha, it turned out, had known her years before.

The newlyweds spent five years at 8412 S. Mannistee in Martha’s mother’s attic, for which they paid ten dollars a month in rent, then bought a house in the area for seven thousand dollars, five thousand of which Martha had set aside.

“There was a steel mill on every corner” on the Southside in those days, Martha said, and, like his father and hers and everyone else on that side of town, Albert worked in one. Then he became a sheet metal worker, installing heating and air-conditioning systems, and ultimately a supervisor for Deslauriers, which supplies services and equipment to the construction industry. He traveled a lot—sometimes he was home only two days a month. He worked in New York, Indiana, Wisconsin, Ohio and Illinois. He worked on the Sears Tower in Chicago, among lots of other high rises, and the state capitol building in Indianapolis. He took great pride in providing for his family.

He was a Bears and White Sox fan, but not a rabid one on either count. Martha said he preferred going on a drive with her to going to a game, but he liked to check the score of any game in progress at the time on the radio.

Albert died of lung cancer 27 December 1993, six months after a quintuple heart bypass. A lifelong smoker, he had quit after being diagnosed two years before, but apparently too late. His daughter Marcia thinks the industrial toxins he had been exposed to as a sheet metal worker may have contributed to his demise. He was seventy years old.

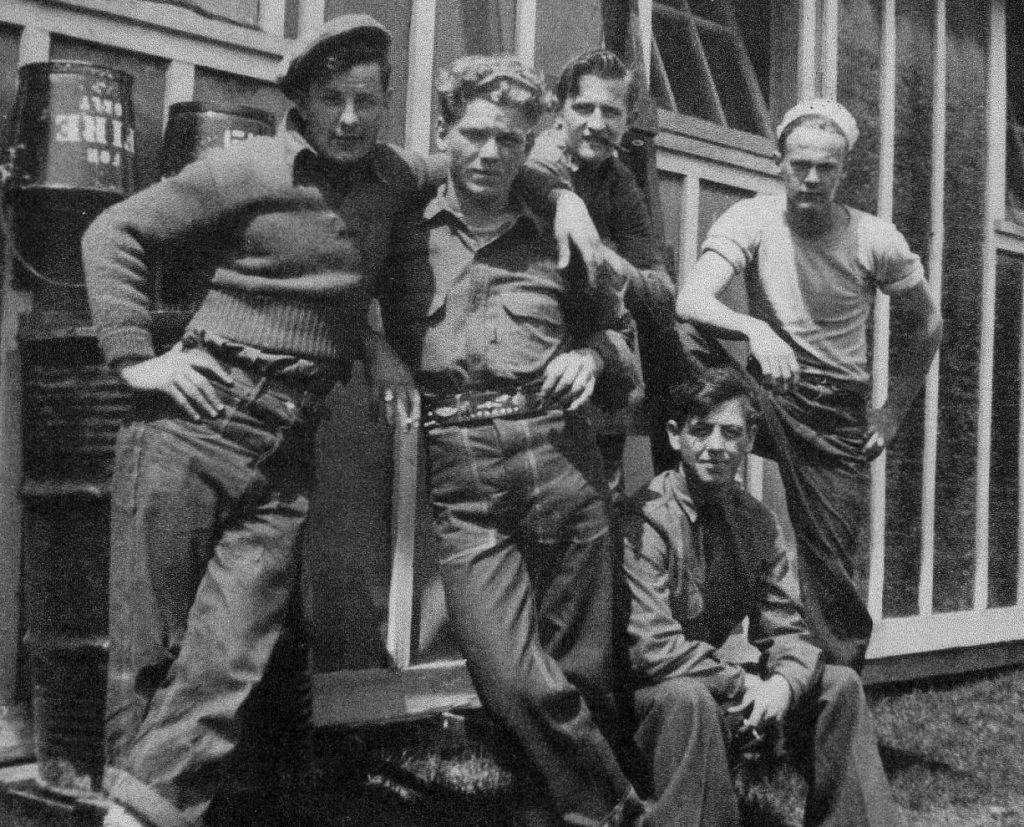

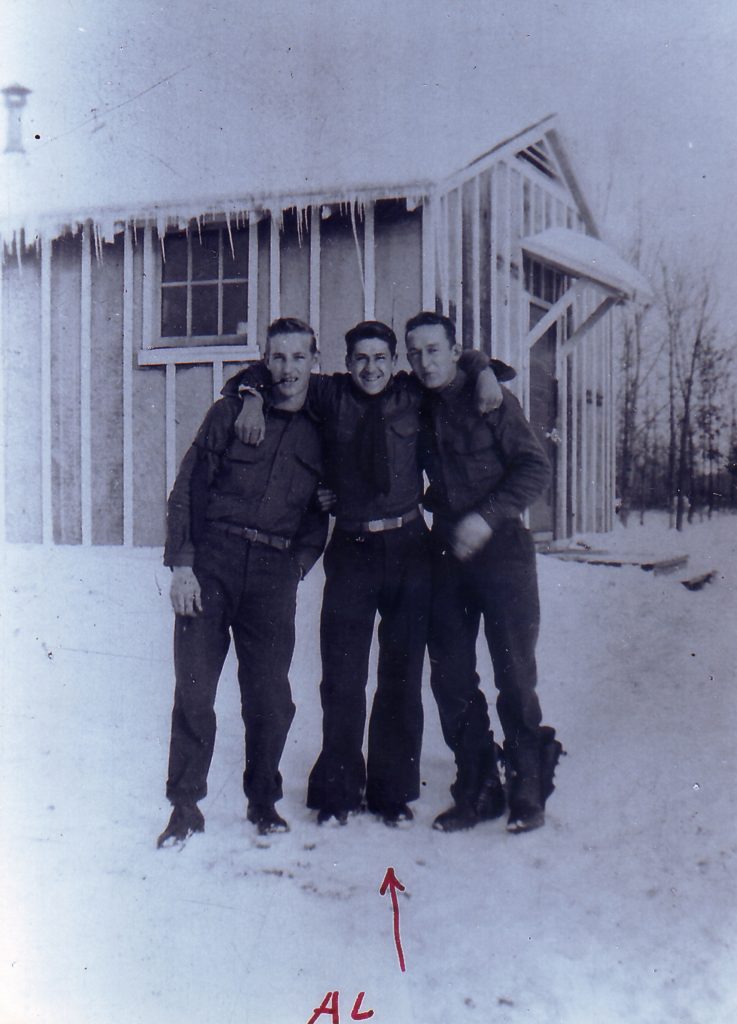

The photos below of Albert Bolke and fellow Camp Rusk CCC workers c. 1940-41 appear courtesy of the Bolke family.

Martha died 16 April 2021 at age 97. Al and Martha are survived by their children Albert Jr., Marsha, Penny and Carl, and numerous grandchildren and great-grandchildren.