About this site

The USS Macaw (ASR-11) was a Chanticleer-class submarine rescue vessel that served, briefly, in the Pacific during World War II, ran aground on the reef at Midway Atoll on 16 January 1944 attempting to rescue its first submarine, and sank amid an episode of freakishly huge waves four weeks later. There was a salvage crew of 22 men aboard the ship when it sank. Five of those men, including the Macaw’s captain, Lt. Cmdr. Paul Willits Burton, USN, and four enlisted men died that day. So did three sailors from Midway NOB (naval operating base), who effectively sacrificed themselves to those waves in a pair of rescue attempts they had been expressly ordered not to undertake.

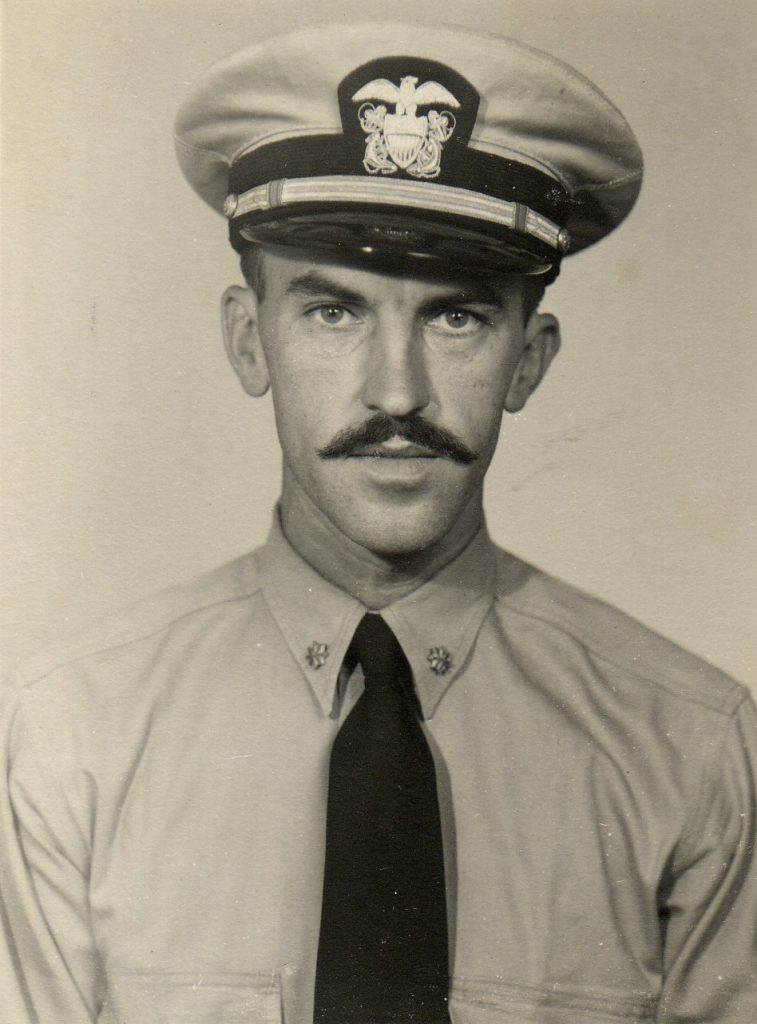

My father, Lieut. Gerald F. “Bud” Loughman, was the Macaw’s executive officer. As the senior surviving officer after it sank, he was charged with handling much of the paperwork attendant on the loss of the ship. After he died on 28 December 1998, my sister discovered his files concerning the Macaw in a box of his papers. In those files were his own account of the sinking and those of all his fellow sinking survivors, all written within days of the event, and photos of the ship and its crew taken before it sank and after.

Those files and photographs sparked my interest in a story I had gotten some of from my father over the years but had only just scratched the surface of. In reading his files, I found that my father’s recollections of the sinking, as he had related them to me, were not entirely accurate. This should not have come as a great surprise to me. I am now about the age my dad was when I grilled him about events fifty years in the past, and I am now often hard-pressed to remember what I ate for breakfast. Traumatic events tend to inscribe themselves more indelibly on one’s memory than banal ones, but it’s easy to see how, amid the confusion and excitement of an experience as harrowing as the one those 22 men underwent, one might register impressions that don’t correspond exactly with reality, or how, in drawing on one’s memory half a century later, one might recall things that didn’t actually happen, or happen quite as one recalls them.

My dad recalled that, after getting swept off the Macaw in the wee hours of 13 February 1944, he spent the rest of the night on a buoy with a shipmate who repeatedly vomited on my dad’s back, something that pleased my dad inasmuch as it afforded him the only warmth he experienced during his several hours there. All that was apparently true. My dad was definitely on the buoy with a shipmate, and the shipmate, by his own account, was prone to seasickness, a condition being on that buoy that night would have been highly conducive to. Where my dad’s recall erred was in regard to the other man’s identity. My dad recalled him as Electrician’s Mate Charles Kumler. Kumler was in fact one of the twenty enlisted on the ship that night, but when my dad was on the buoy, Kumler and five other men, two of them injured, were floating, limbs entwined, in a circular support group a half mile or so away, and Kumler was slipping into shock.

The other man on the buoy that night was in fact Shipfitter Nord Lester. Lester was easy for me to locate. According to the people finder sites I consulted, he was the only Nord Lester in the United States. I called him up and said I thought he had spent a night on a buoy with my dad in 1944. He responded, “Sure did.” Lester was the first of eighteen Macaw crewmen I contacted over the ensuing twenty years or so. At some point during those years—within the first two or three, I think—I decided to write a book about the Macaw, its captain, and its crew.

Through the good offices of the University Press of Kentucky, which graciously consented to publish it, that book—A Strange Whim of the Sea: The Wreck of the USS Macaw—is available for purchase through various online sellers, of which my favorite is Bookshop.org, a nonprofit organization which donates a significant share of the proceeds from every purchase to the brick-and-mortar independent bookstore of the buyer’s choosing.

I envision this website as a sort of companion piece to the book. It replaces, after an inexcusably long interval, an earlier site by almost the same name (dot org instead of dot net) that vanished from cyberspace after I neglected one year to pay the fee to keep it active. I propose in this new site to duplicate neither that old site nor the book, but perhaps to enlarge on various topics I touch on in the book, or perhaps to pursue others I don’t mention there at all, topics more or less directly related to the Macaw or to one or more of the men who served aboard it. My main focus initially will be to post photographs I didn’t have room for in the book. I’m not sure at this point what the scope and drift of this site will be. Time and my inclinations will tell. Meanwhile, if you have any questions to ask or information to offer about the ship or the men who served aboard it, please do not hesitate to contact me at timloughman@ussmacaw.net.

Welcome aboard …

A brief history of the ship

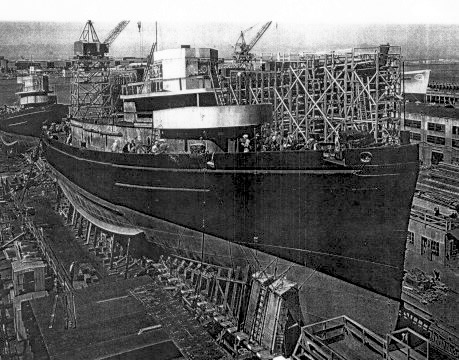

The USS Macaw (ASR 11) was a Chanticleer-class submarine rescue vessel built in 1941-42 by the Moore Dry Dock Company at the foot of Adeline Street in Oakland, California. (ASR stands for Auxiliary—Submarine Rescue. The Chanticleer was the prototype of the class.)

The bill for the construction of the Macaw, her sister ships—Chanticleer, Coucal, Florikan and Greenlet—and a pair of submarine tenders was the then princely sum of $37,630,000.

The Macaw and its sister ships were among the navy’s first submarine rescue vessels built as such. Most or all of the preexisting ASRs in the fleet were converted minesweepers. The new ASRs were essentially big, armed ocean-going tugs each furnished with a 9,500-pound diving bell called a McCann rescue chamber, a boom capable of lifting twenty tons to deploy it, a decompression chamber for deep-sea divers, and other equipment to aid in salvaging sunken or otherwise stranded submarines and rescuing their crews.

The Macaw was laid down in Oakland on 15 October 1941. Sponsored by Miss Vanessa Easton of neighboring Berkeley, the ship was launched in tandem with the Greenlet 12 July 1942 and commissioned exactly one year later under the command of Lt. Cmdr. Paul Willits Burton, a resident of Asbury Park, New Jersey, and graduate of the US Naval Academy, class of 1933.

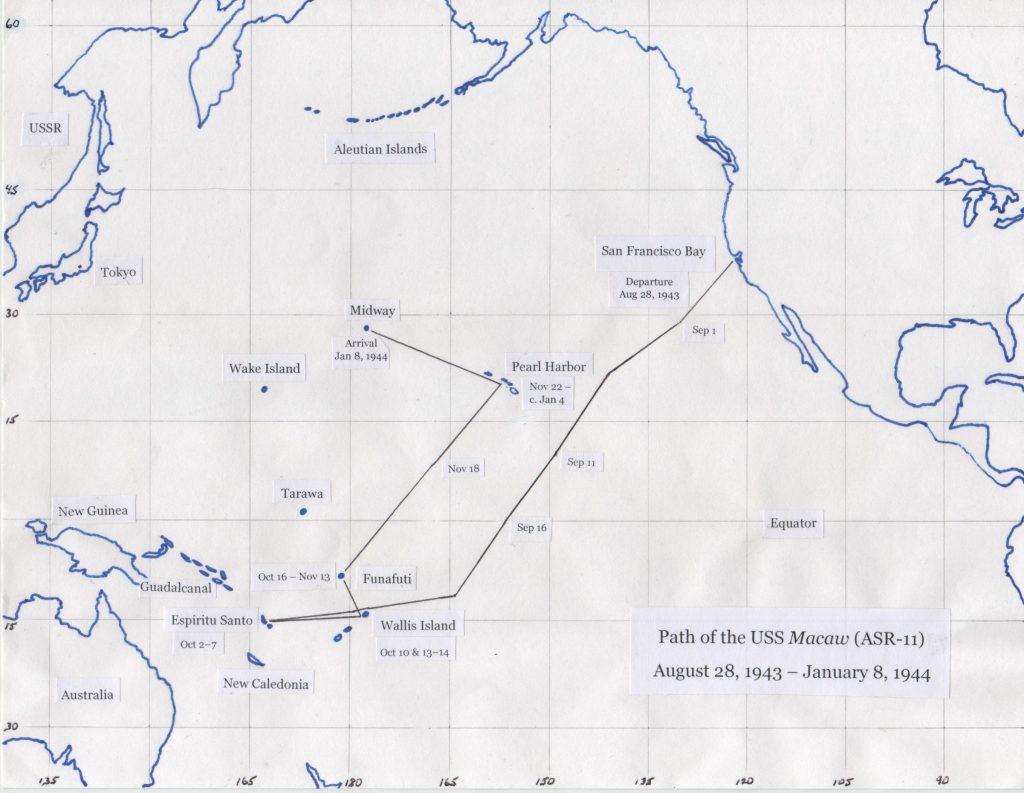

After a roundtrip shakedown cruise to Monterey, the Macaw left San Francisco Bay on 28 August 1943 in convoy with a group of eight Liberty ships, two minesweepers, five barges and a yard tug. Each Liberty ship towed a section of an enormous prefabricated floating dry dock, ABSD-1 (ABSD stands for Advanced Base Sectional Dock), which was to be assembled at Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides, 1,300 miles northeast of Brisbane, Australia.

The Macaw arrived at Espiritu Santo on 2 October 1943, then proceeded by way of Wallis Island, Funafuti and Pearl Harbor to Midway, where it arrived 8 January 1944. Eight days later the Macaw ran aground attempting its first rescue of a submarine, the USS Flier (SS-250), which had grounded on the reef attempting to enter the channel to the lagoon amid heavy seas about two hours before. The Flier was pulled from the reef six days later and towed to Pearl Harbor. The Macaw remained stuck for four weeks, during which salvors struggled unsuccessfully amid generally rough seas to tug it free. On the night of 12-13 February the Macaw gradually slid backward into deeper water amid extremely high seas and sank. About 0230 on the 13th, facing simultaneously the prospects of drowning and asphyxiation, the 22 men aboard left the pilot house, in which they had sought refuge, and tried to climb the foremast, which still projected from the sea. Three of them succeeded. Most of the rest were swept overboard. Five of the men, including Paul Burton, died. So did three sailors from NOB Midway in a pair of unauthorized rescue attempts later that morning. The Macaw came to rest at the eastern edge of the mouth of the channel, partially obstructing it. To minimize the hazard the wreck posed to navigation, a demolition team from the USS Shackle (ARS-9) spent much of the following six months blowing away its superstructure. The hull of the Macaw remains about where the ship sank.

Midway Atoll ca. 1943. View is from the southwest. Sand Island is in the foreground, Eastern Island in the background. Brooks Channel runs due north and south between them. (USN photo courtesy NARA)

Midway Atoll ca. 1943. View is from the southwest. Sand Island is in the foreground, Eastern Island in the background. Brooks Channel runs due north and south between them. (USN photo courtesy NARA)

Macaw and Flier, 16 January 1944. In this photo, taken from a vessel at the mouth of Brooks Channel the afternoon the two ships ran aground, the Macaw appears to be angling toward the Flier. In fact, they came to rest almost exactly parallel to each other, facing opposite directions, about a hundred yards apart. The vessel in the distance at right may be a yard tug, YT-188. (Photo courtesy USN/NARA)

Macaw and Flier, 16 January 1944. In this photo, taken from a vessel at the mouth of Brooks Channel the afternoon the two ships ran aground, the Macaw appears to be angling toward the Flier. In fact, they came to rest almost exactly parallel to each other, facing opposite directions, about a hundred yards apart. The vessel in the distance at right may be a yard tug, YT-188. (Photo courtesy USN/NARA)

Flier and Macaw aground at Midway, 17 January 1944. The Flier grounded first. By the time the Macaw followed suit in just about the same spot two hours later, the Flier’s captain, Cmdr. John D. Crowley, had succeeded in turning the sub about to face into the waves, and the current had pushed it about a hundred yards east along the reef. The Macaw came to rest more conventionally bow forward. (USN photo courtesy NARA)

Flier and Macaw aground at Midway, 17 January 1944. The Flier grounded first. By the time the Macaw followed suit in just about the same spot two hours later, the Flier’s captain, Cmdr. John D. Crowley, had succeeded in turning the sub about to face into the waves, and the current had pushed it about a hundred yards east along the reef. The Macaw came to rest more conventionally bow forward. (USN photo courtesy NARA)

The seaplane basin at Midway, 29 January 1944. The Contractors’ Tower, a converted water tank from which Captains Joseph Connolly and Charles Edmunds would monitor the sinking of the Macaw two weeks later, appears at the middle of the lower edge of this photograph. Eastern Island appears in the background. The Macaw lay pinned to the reef at the time just out of view to the right. (USN photo courtesy NARA)

USS Macaw, 14 February 1944. The tall structure at left is the foremast. Projecting from it just above the surface is the forward searchlight platform, from the railing of which Steward’s Mate Robert Vaughn had been swept to his death the day before. Just above the crossing spar two-thirds of the way up the foremast is the crow’s nest, in which Seaman Edward Wade and Bosun’s Mate Charles Scott took refuge as the ship sank. Seaman George Manning clung that night to the ladder that climbed the mast, probably just below them. Machinist’s Mate Erwin Knecht rode out that night atop the tripod, the triangular structure aft. All of the other 22 men aboard when the ship sank were swept overboard. Five of them, including Vaughn and the captain, Lt. Cmdr. Paul W. Burton, died, as did three of four would-be rescuers from Naval Operating Base Midway who went out to the sunken ship in rearming boats, two men in each of two boats, the morning of 13 February. Both boats overturned. (USN photo courtesy NARA)