San Francisco Bay, on the shore of which the USS Macaw was built and from which it sailed off to war and disaster in 1943, has come and gone at least four times over the last 500,000 years or so, vanishing during cold spells, when much of the precipitation that falls on land stays there in the form of ice and sea level falls, and reappearing during warm spells when that ice melts and sea level goes back up. The current bay has been around for only about eight thousand years, a small fraction of the blink of an eye in geological time. And much of it having been filled in for development, it’s only about two-thirds the size it was before the Gold Rush brought industrial civilization to its shores.

What we call San Francisco Bay is actually three bays: the bay its namesake city sits on, San Pablo Bay to the northeast, and Suisun Bay east of that. The latter two are submerged river valleys, the river in question comprising the combined flow of the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers, which drain the northern and southern reaches respectively of the Sierra Nevada, California’s spinal mountain range, and merge now about where they enter Suisun Bay. During cold spells when there is no bay, that river roughly describes an S curve from the narrow Carquinez Strait, through what is now San Pablo Bay, where the Napa and Petaluma rivers join it, past the range of hills that form today’s Tiburon Peninsula, and through a rocky gorge known today as the Golden Gate, then heads more or less straight west, discharging at last into the Pacific Ocean a few miles beyond what are coastal hills during those cold spells and are now the Farallon Islands, thirty miles offshore.

The more constricted its channel, the faster water flows, and the greater erosive force it flows with. The constricting presence of the Tiburon range may help account for the fact that the episodic river, while skirting it in multiple stretches of tens of thousands of years, has carved just off the northeast shore of the Tiburon Peninsula a channel that lies now at a depth of about 35 feet, considerably more than the bay’s average of just twelve to fifteen feet, and deep enough to provide anchorage for all but the most heavily laden ocean-going ships.

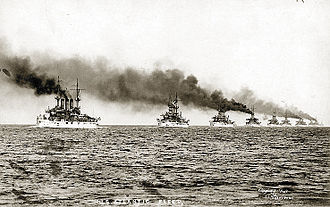

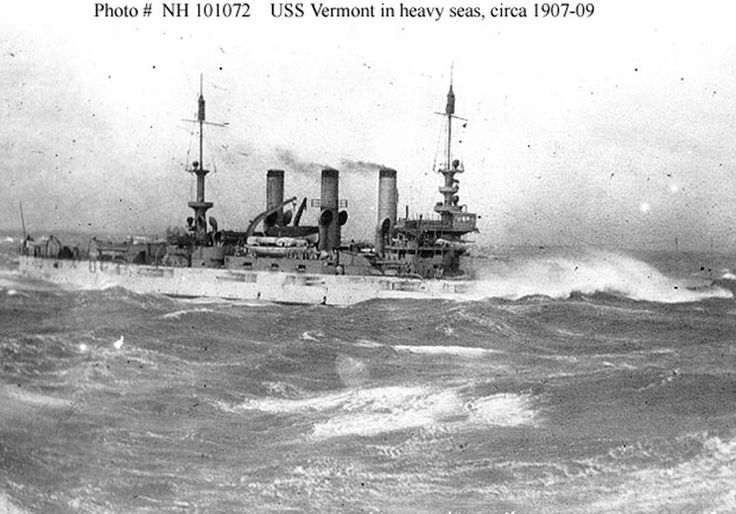

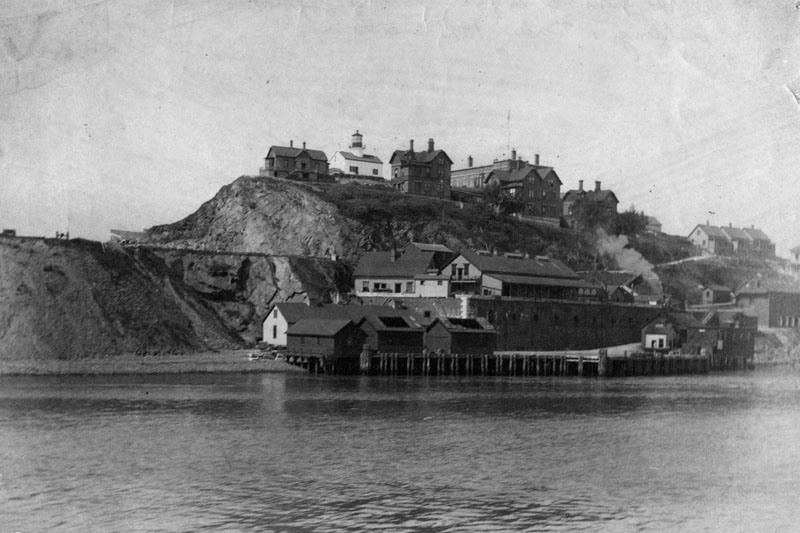

That anchorage attracted industry to the Tiburon Peninsula amid the regional population explosion triggered by the California Gold Rush. A cod-packing firm set up shop on the peninsula ca. 1877, then pulled up stakes in 1904 and sold the property to the Navy, which built a coaling depot on it. The Great White Fleet, a flotilla of sixteen battleships President Theodore Roosevelt sent around the world to impress upon friend and foe alike the United States’ emergence as a naval power to be reckoned with, refueled there in 1908. By 1931, oil having replaced coal as the Navy’s fuel of choice, the coaling station was shut down and the site occupied by the newly created California Nautical School (subsequently renamed the California Maritime Academy), a state facility for training officers for the merchant marine.

John A. Roebling’s Sons, the New Jersey firm founded by the Prussian immigrant, engineering genius and one-time utopian communal farmer who conceived of and designed the Brooklyn Bridge, moved in next door ca. 1935 and set about stringing the suspension cables for the Golden Gate Bridge. The firm, for many years the world’s leading supplier of suspension cables, had been allotted twelve months to complete the work. They did it in just over six months.

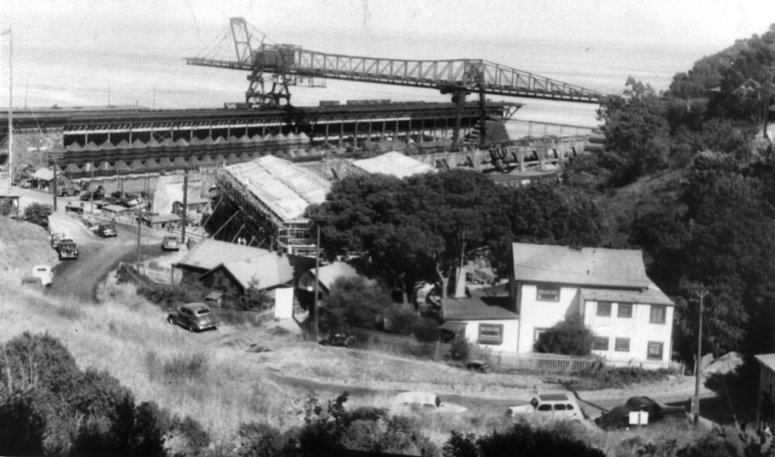

In 1940, as war clouds loomed, the Nautical School moved about twenty miles northeast to Vallejo, and the Navy reclaimed the old coaling station site and began manufacturing submarine nets on it. (In 1942 it bought the adjacent Roebling’s Sons’ nine-acre site and expanded the operation.)

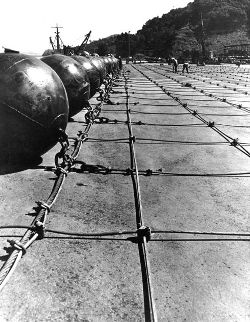

A submarine net is a sort of flexible underwater chain link fence designed to bar passage to submarines. During the war Navy deployed submarine nets made by the Tiburon Net Depot (assisted by inmates at the high-security federal prison on nearby Alcatraz) up and down the West Coast and throughout the Pacific.

The Net Depot’s biggest net was the one that protected San Francisco Bay itself. Installed shortly before the attack on Pearl Harbor at an oblique angle to the newly completed Golden Gate Bridge and about three quarters of a mile inside it, the San Francisco Bay net consisted of steel wire mesh held in place by concrete anchors and buoyed up by hundreds of spherical steel floats almost five feet in diameter. It weighed six thousand tons and stretched seven miles from San Francisco to Sausalito.

During the war there actually was a gate just inside the Golden Gate in the form of a section of that net. Four net tenders, two moored at either end of the gate section, opened and closed it by means of winches to let authorized traffic come and go.

The authorized outbound traffic on 28 August 1943 consisted largely of Task Group 116.11, a group of 26 vessels, including eight Liberty ships each towing a section of an enormous ten-section prefabricated floating drydock, which the Macaw was to lead in convoy from that same anchorage off the Tiburon Peninsula to the US base at Espiritu Santo, 5,865 miles away in the South Pacific.

Getting into or out of San Francisco Bay was a delicate undertaking at the time owing to the presence just outside the Golden Gate of more than six hundred mines. But proceeding single-file past Angel Island and Alcatraz and under the bridge, by about 5 pm all 26 vessels in the convoy had negotiated that passage unscathed and proceeded off to war in a column more than thirty miles long.

Sources

MilitaryMuseum.org, “Historic California Posts, Camps, Stations and Airfields: Naval Net Depot, Tiburon”

“Tiburon Naval Net Depot History” by Justin M. Ruhnge, Goleta Valley Historical Society

Wikipedia

World War II Database

“World War II in the San Francisco Bay Area” by John Martini (nps.gov/nr/travel/wwiibayarea/text.htm#seacoastdefense)]