By the time Paul Burton was assigned to the USS Tarpon (SS-175) in July 1942, the submarine had acquired a reputation as a bad-luck boat. In four war patrols it may or may not have sunk one ship, a freighter whose sinking was not confirmed. The fifth patrol, from 22 October to 10 December 1942, with two new officers atop the command structure in Burton and the captain, Lt. Cmdr. Thomas Lincoln Wogan, went no better, but the sixth (10 January to 25 February 1943), in which the Tarpon sank two Japanese ships, a freighter and a troop transport, was the second most productive by tonnage among all US submarines in the war to that point.

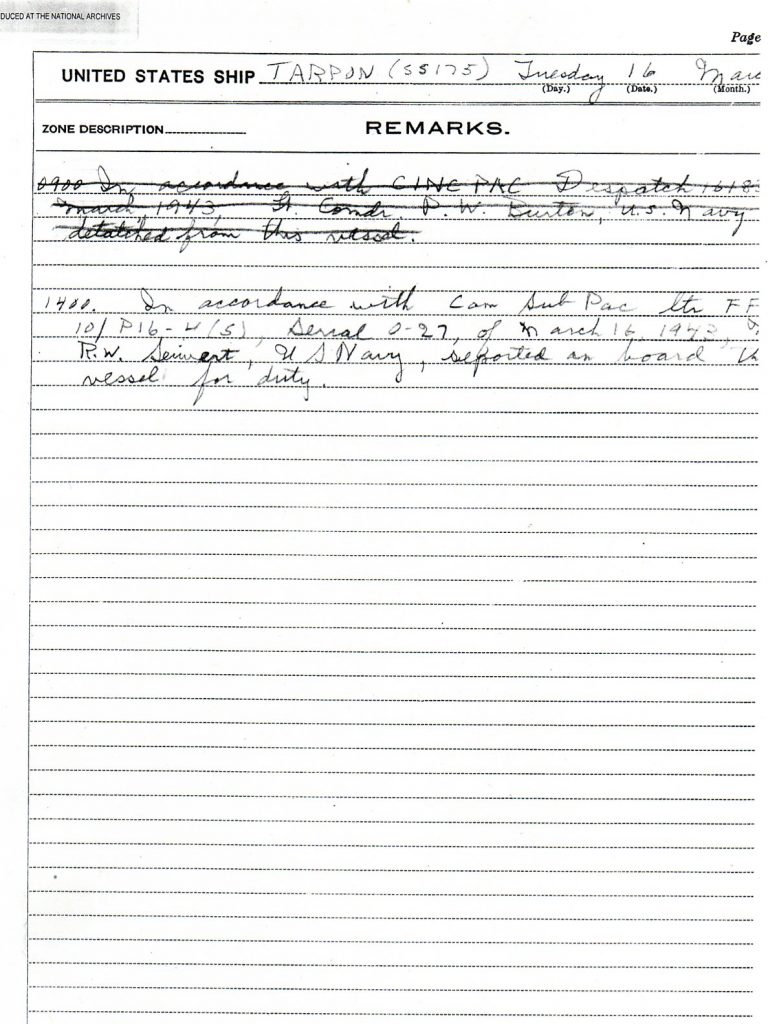

Upon the conclusion of that patrol Wogan, for reasons not entirely clear, recommended to the brass at Pearl Harbor that Burton be “blackballed” i.e., expelled, from submarine duty, and he was. In keeping with a practice apparently not uncommon during the war, as a submarine officer deemed unequal to the task of commanding a submarine, he was assigned instead to the command of a submarine rescue vessel, in his case the Macaw. Going from second in command of one vessel to command of another might appear to be a promotion, but in fact for Paul Burton it was a painfully humiliating rejection.

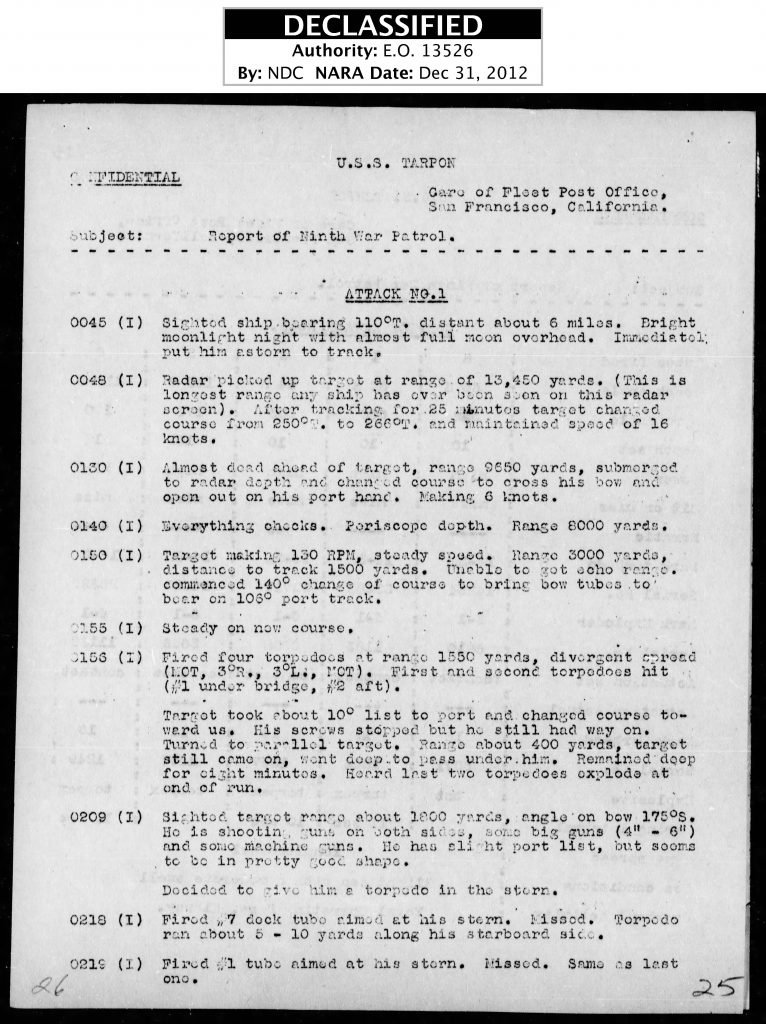

Wogan commanded the Tarpon for another three patrols, its seventh, eighth and ninth. During the ninth (1 October to 3 November 1943), while patrolling at night off the coast of Japan, the Tarpon crossed paths with a surface vessel that fit the profile of no ship Wogan or any of his subordinates was familiar with, Japanese or otherwise. Proceeding on the safe assumption that no Allied surface vessel would be operating in Japanese waters at that point in the war, Wogan torpedoed the stranger. With the release after the war of Axis naval records, it came out that his victim that night was German, the Michel, a merchant raider, basically a warship in the guise of a noncombatant cargo vessel.

The Michel, having operated in the South Atlantic and sunk fifteen Allied vessels earlier in the war, had shifted to the Pacific after the German high command decided that the Atlantic had become too dangerous for surface ships. It was returning on the night of 16 October 1943 to its adopted home port of Yokohama after sinking three more Allied ships—all three, strangely enough, Norwegian—in a counterclockwise loop around Australia, to the coast of South America and almost back to Japan when it had the misfortune of crossing paths with the Tarpon.

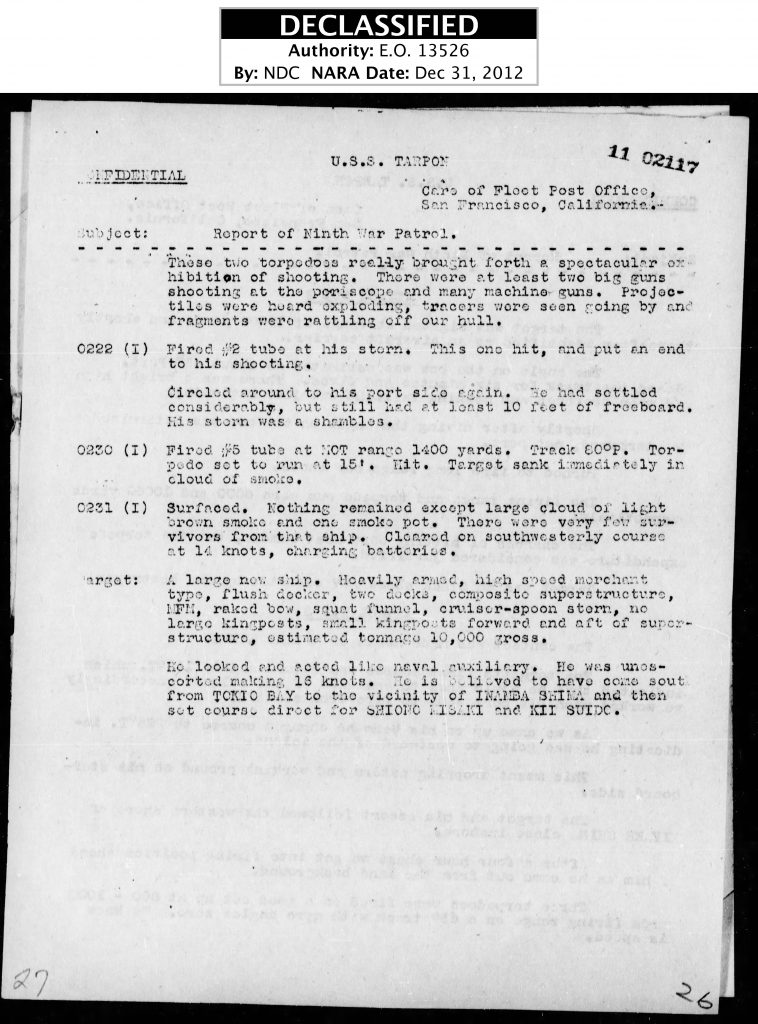

The report on the Tarpon’s ninth patrol, presumably written by Wogan himself, purports to describe the scene of the sinking as the Americans found it upon surfacing immediately afterward:

0230

Fired #5 tube at MOT range 1400 yards. Track 80˚P. Torpedo set to run at 15’. Hit. Target sank immediately in cloud of smoke.

0231

Surfaced. Nothing remained except large cloud of light brown smoke and one smoke pot. There were very few survivors from that ship. Cleared on southwesterly course at 14 knots, charging batteries.

In fact there were more than a hundred and possibly as many as two hundred survivors from the Michel, at least some of whom must have been visible enough within minutes after it sank. One hundred and sixteen men made it to the coast of Japan after three days afloat in lifeboats. Alerted to the presence of scores of others on rafts or clinging to debris, the Japanese reportedly claimed later to have conducted a search and found no one. German officers in Japan are said to have had their doubts about how diligently their hosts had conducted their search, if they conducted one at all.

Why Wogan would have wanted to gloss over the presence of survivors in the water is unknown. Perhaps he sought to avoid blame for not picking them up, though in fact it was not common in the war in the Pacific, if it was anywhere, for either side to treat the other with empathy, and his submarine would have lacked the capacity to take aboard more than a fraction of the Michel survivors in any case.

Tom Wogan was transferred after that patrol to command of the USS Besugo (SS-321), under construction at Electric Boat in Connecticut. He commanded it through its first three war patrols, assumed command of a submarine division in July 1945, served in Albuquerque, New Mexico, after the war, and committed suicide in San Diego on 17 March 1951, the day before he was scheduled to take command there of Submarine Squadron 5.

The Tarpon did three more war patrols, served after the war as a training ship, and sank 26 August 1957 off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, under tow to a scrapyard.

Sources

German auxiliary cruiser Michel, Wikipedia

“Navy Hero Kills Self Following Promotion,” The San Diego Union, 17 March 1951, p. A-1

“Pacific Sub Hero Is San Diego Suicide,” Stars and Stripes, 22 March 1951, p. 1

subsowespac.org (defunct website)

“The Last Raider” by John Guttman, World War II Magazine, 19 Aug 1997

U.S.S. Tarpon: Report of Ninth War Patrol

USS Tarpon (SS-175), Wikipedia