A brief history of the ship

USS Flier (SS-250), the submarine that fatefully crossed paths with the Macaw at Midway in January 1944, is the subject of three books—The USS Flier: Death and Survival on a World War II Submarine by Michael Sturma; Eight Survived by Douglas A. Campbell; and Surviving the Flier by R. J. Hughes. The story of the Flier deserves multiple tellings; it’s among the most extraordinary in all the annals of submarine warfare in World War II. The US lost 52 submarines during the war, all but four of them in the Pacific, and in every case when the loss of the boat was a direct result of enemy action, as opposed to scuttling, the entire crew was either killed or captured when the boat sank. The one exception was the Flier.

The Flier was built by the Electric Boat Company in Groton, Connecticut. Commissioned October 18, 1943, Lt. Cmdr. John D. Crowley in command, the Flier proceeded to Pearl Harbor via the Panama Canal, narrowly avoiding disaster en route when an armed US merchant vessel mistook it for an enemy sub off Panama and fired thirteen shells. Owing perhaps to an obscuring rain squall, none of them struck home.

The Flier left Pearl Harbor for what was to have been its first war patrol on 12 January 1944 and was attempting to negotiate the entrance channel to the lagoon at Midway amid heavy swells and a strong current four days later to top off there on fuel when it ran aground at the eastern edge of the mouth of the channel.

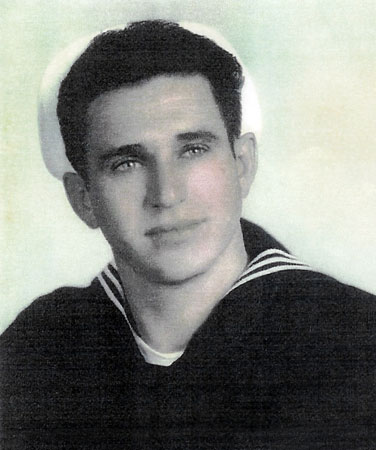

By dint of some desperate maneuvering, Crowley managed to turn the boat around to face into the massive swells threatening to capsize it and drown its entire crew. To maintain that heading, he sent a party of five sailors forward on the deck to help release a bow anchor. Two of them, Torpedoman’s Mate 3/c James Francis Peder Cahl of South Holland, Illinois, and Torpedoman’s Mate 1/c Clyde Gerber of Slayton, Minnesota, were swept overboard. A third, Fireman George Banchero of San Jose, California, stripped off his outer garments, grabbed a life ring, leapt in after Gerber, and managed, after a struggle he later estimated to have lasted two and a half to three hours, to escort Gerber to shore. At some point in the ordeal Gerber sustained a broken arm. James Cahl drowned.

Having arrived at Midway eight days before, the USS Macaw (ASR-11) was sent out to get a tow line to the Flier and promptly ran aground itself right about where the Flier had first struck, at the eastern edge of the channel entrance. The Flier having been swept eastward along the reef while swiveling about, the two ships came to rest parallel to each other, pointing opposite directions, about a hundred yards apart.

Pulled off the reef a week later, the Flier was taken in tow by the USS Florikan (ASR-9), sister ship to the Macaw, back to Pearl Harbor. The towline parted en route amid heavy seas and was reconnected in a delicate piece of maneuvering that took about eight hours, during which both vessels were at risk of foundering or colliding or both.

After repairs at Mare Island on San Francisco Bay, the Flier finally did conduct a war patrol, off Manila in the Philippines, in May and June 1944, during which it was credited with sinking four Japanese merchant vessels. That first patrol terminated at Fremantle, Australia. The second was to take the sub to the waters off Vietnam.

It was headed there, transiting the Balabac Strait between Borneo and Palawan, the southwesternmost major island of the Philippines, on the surface about 2200 on 13 August when it struck a mine. Bud Loughman, the executive officer of the Macaw, said he heard later that the Flier had executed an otherwise picture-perfect dive minus the forward third of its hull.

Nine men, including Capt. Crowley, were topside when the blast occurred. None of them, in keeping with submariner tradition, was wearing a life vest. Fourteen men initially survived the sinking. Conditions could have been worse—warm seas with a gentle swell of about a foot—but the water was thick with oil, and visibility, under an overcast sky that would remain moonless until about 0300, was almost nil. The oil made it problematic for the men to open their eyes, and when they did, they could hardly see. Aside from glimpses of landforms silhouetted by occasional flashes of lightning, they had nothing to steer by.

The initial survivors congregated in the water, conducted a sort of roll call and discussed their options. The nearest island, Comiran, lay about three and a half miles away, but they suspected that it was occupied by the Japanese, at whose hands it was not uncommon for POWs to be beheaded. They decided to strike out for more distant coral reefs to the northwest. Accounts vary as to whether they set off promptly or chose to tread water for part or all of the five or so hours until moonrise.

Within about twenty minutes one of the party had lost consciousness and slipped beneath the waves. As the ordeal wore on five other men followed suit, at least one apparently by volition. Having inquired at some point about the remaining distance to their destination and gotten what was, in fact, an underestimate of five to six miles, the chief gunner’s mate is said to have replied “All right, then, fuck it,” and swum off at an angle. He was never seen again.

As the day dawned, the sea grew rougher and some of the men still swimming got separated from the others. Five of them ended up clinging to a floating palm tree. Using palm fronds as paddles, they got to within about half a mile of Mantangule Island and were able to walk the rest of the way ashore, where they were greeted by Quartermaster 3/c James Dello Russo, who had swum unaided the whole way. They had been in the water about eighteen hours (Russo slightly less) and swum about twelve miles—and probably then some given that they could hardly have negotiated a straight line.

That evening the executive officer, Lieut. James Liddell, went in search of food and water and found Fire Controlman 2/c Donald Paul Tremaine. About a day later Motor Machinist’s Mate 3/c Wesley Bruce Miller walked into the little encampment the others had made. Eight men had survived.

Their troubles were not over. There was no water on the island and almost nothing to eat. Of hundreds of coconuts they found on the beach that first day, all but one were spoiled. They built a raft of bamboo and vines and set about island hopping, aiming for the major island of Palawan. The two men deemed strongest among them, Russo and Radio Technician Arthur Gibson Howell, sat on the raft and paddled. The others clung to it, walking when the water was shallow enough.

They subsisted for the better part of a week on a few coconuts. Most or all of them had stripped to their underwear during their swim, so they were almost naked. They suffered from hunger and sunburn, from cold at night, when they would burrow into the sand to try to keep warm, only to shake it off with their shivering; from muscle cramps and insect bites and abrading their feet on the coral, and from fear of sharks—they spotted at least one shark, and must have figured the sharks would have little trouble finding them with their bleeding feet.

But mostly they suffered from thirst. Besides what few raindrops they managed to catch in seashells or their open mouths, for almost five full days they had no water to drink.

Finally, about 1700 on August 18, they got to Bugsuk Island, where they encountered a group of sympathetic indigenous guerrilla fighters, one of whom spoke enough English to warn them, apparently in something like the nick of time, not to drink from a cistern the Americans had discovered at an abandoned plantation house—it had been poisoned with the Japanese in mind. That information came too late for at least one member of the Flier party. He got sick but survived.

On August 31, shortly after midnight, two borrowed boats bearing the Flier survivors and a number of civilian evacuees rendezvoused with the USS Redfin (SS-272) just offshore from Brooke’s Point, Palawan. They arrived in Darwin, Australia, five days later. Fire Controlman Tremaine exhibited symptoms of malaria en route. His shipmates got back to Allied territory in basically good health.

Alvin Jacobson, of Grand Haven, Michigan, the last living survivor of the Flier, died in 2008 at the age of 86. Jacobson had alternated between breast stroke and side stroke in his swim from the sunken Flier 64 years before. In his later years he spearheaded a campaign to locate the wreck. With the ongoing assistance of his family, that effort bore fruit shortly after Jacobson’s death. On February 1, 2010, the Navy announced that a submarine that had been found on the floor of the Balabac Strait was the Flier.

A memorial service to honor the men of the Flier was held in August 2010 at the Great Lakes Naval Memorial and Museum in Muskegon, Michigan. Among those in attendance was 83-year-old James Alls of Independence, Kentucky. Alls had served as a motor machinist’s mate aboard the Flier on its first patrol, and as an MP during the sub’s stay in Fremantle. In this latter capacity he was tasked with enforcing a 5 pm curfew on American sailors patronizing bars in neighboring Perth.

While escorting a fellow American from one such bar he suffered a broken jaw courtesy of a hostile, beer mug-wielding New Zealander. He was recuperating in a medical facility when the Flier left Fremantle on its ill-fated second patrol. Alls had been left behind. His Kiwi assailant had saved his life. The experience left Alls with a troubling case of survivor’s guilt. At the memorial service exactly 66 years later he represented Fireman 1/c Donald Nesser See of Columbus, Ohio, the sailor who had taken his place. See died when the boat went down.

Sources:

• Clay Blair, Jr. Silent Victory: The US Submarine War Against Japan, Vol. 2 (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1975), p. 564

• Douglas A. Campbell, Eight Survived: The Harrowing Story of the USS Flier and the Only Downed World War II Submariners to Survive and Evade Capture (Guilford, CT: Lyons Press, 2010)

• Al Dobbins, torpedoman aboard the USS Florikan, January 1944; interviewed 22 Feb 2012

• Cmdr. John D. Crowley, USN, “Narrative of Second War Patrol of U.S.S. Flier.”

• Cmdr. Gerald F. Loughman (ret.), USNR, interviewed December 1991

• Eugene D. McGee, “To Sink and Swim: The USS Flier” in Submarine Review, October 1996

• James L. Mooney, ed., Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Vol. 2, C-F, (WDC: Naval History Division, 1959-81), p. 416

• Michael Sturma, The USS Flier: Death and Survival on a World War II Submarine (Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky, 2008)

• The National Gold Star Family Registry

• Muskegon Chronicle on-line: photos.mlive.com/muskegonchronicle/2010/08/uss_flier_memorial_ceremony_1.html